Review of Rough Winds: Extreme Weather and Climate Change by James Powell

Posted on 23 September 2011 by Anne-Marie Blackburn

The perennial question following any extreme weather event is whether climate change is responsible for the event in question. Until recently, the short answer to this question was 'No' but recent findings suggest that this answer needs to be refined. It is still not possible to state categorically that climate change has caused a specific event, and natural variability continues to play a key role in extreme weather. But climate change, through rising temperatures and water vapour levels for example, is changing the odds of extreme events occurring. The last couple of years have certainly seen a large number of extreme events take place, from the floods in Queensland, Colombia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, to the droughts in Texas, Australia, China and the Amazon, and record-setting high temperatures in countries that cover approximately one-fifth of the Earth's surface. Wildfires, snowstorms, tornadoes and hurricanes have also made the headlines in a number of countries. This has led to the appearance of new expressions: 'global weirding' and 'a new normal'.

The perennial question following any extreme weather event is whether climate change is responsible for the event in question. Until recently, the short answer to this question was 'No' but recent findings suggest that this answer needs to be refined. It is still not possible to state categorically that climate change has caused a specific event, and natural variability continues to play a key role in extreme weather. But climate change, through rising temperatures and water vapour levels for example, is changing the odds of extreme events occurring. The last couple of years have certainly seen a large number of extreme events take place, from the floods in Queensland, Colombia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, to the droughts in Texas, Australia, China and the Amazon, and record-setting high temperatures in countries that cover approximately one-fifth of the Earth's surface. Wildfires, snowstorms, tornadoes and hurricanes have also made the headlines in a number of countries. This has led to the appearance of new expressions: 'global weirding' and 'a new normal'.

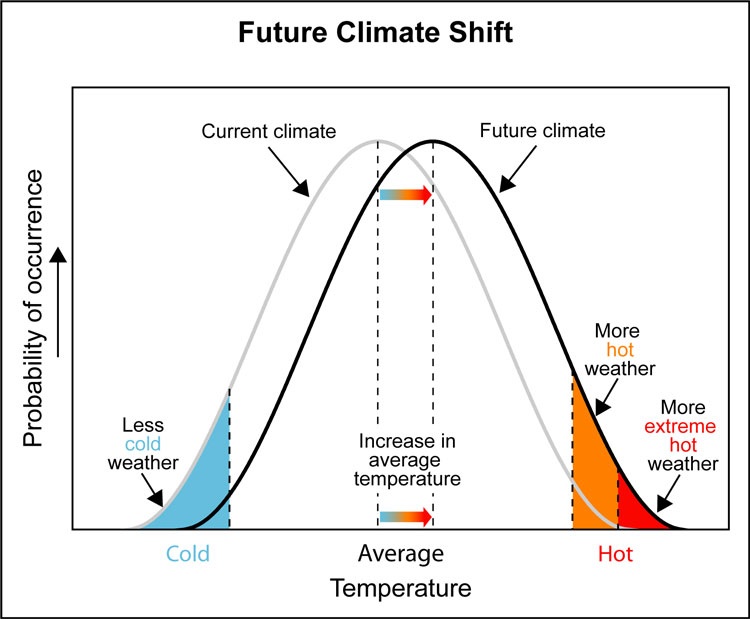

It is within this context that Dr James Powell, whose book 2084: An Oral History of the Great Warming is reviewed here, aims to find out whether there is now a 'preponderance of evidence' showing that climate change is truly under way, a situation which he argues warrants a response. He focuses on extreme weather for a number of reasons. Weather is what we experience on a daily basis and is therefore more tangible than some vague notion of climate change in distant countries or futures. Additionally, extreme weather can prove very costly in terms of lives, livelihoods and infrastructures, and we therefore all have a stake in taking preventative measures. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, increases in the occurrence of events such as extreme temperatures are the best harbingers of climate change. This is clearly illustrated in figure 1 below. With this in mind, the author frames the issue as one of risk management and compares it to the insurance industry: we take out insurance not because of a high probability of fire or burglary, but because we stand to lose a lot if we are uninsured and such an event takes place. Similarly, Powell argues, increasing and/or intensifying extreme events would require action to be taken - we should aim to 'avoid the unmanageable and manage the unavoidable'.

Figure 1: Bell curve showing how an increase in average temperatures leads to an increase in hot and extreme weather. Note also that this doesn't mean there'll be no more cold weather: these cold events will become rarer but will not disappear. Source: US Climate Change Science Program / Southwest Climate Change Network

After providing some background on recent events in the prologue, the author explains the science behind climate change and its possible links with extreme weather. This is an important step as it begins to answer the question 'Why are scientists predicting that global warming will cause intensifying and/or increasing extreme weather events?' This then provides a platform from which to analyse and look at the specifics behind recent events. In doing this, Powell shows how science proceeds from a testable hypothesis whose basis, in this case, lies in basic physics: rising temperatures should lead to an increase in water vapour levels. In turn, this additional heat and moisture should provide the perfect setting for the development of more, and more intense, storms. And so the stage is set: the hypothesis and assumptions are described and the case can now be built block by block.

The book is then organised in short chapters that each tackle a specific event or related extreme weather events - heat, drought, fire, rain and snow, floods, tornadoes, and hurricanes. Powell is meticulous in his research and these chapters read like investigative reports, looking at events and placing them in their historical context, before looking at the evidence that helps determine whether climate change has played a role. And like all good scientific reviewers, the author is not afraid to discuss scientific uncertainties and diffculties which make attribution studies such a complex task. But this is more than a simple description of the mechanisms behind extreme weather. Powell discusses the resulting damage and suffering inherent to such events. This helps bring the message home: extreme events are more than abstract physical phenomena. They are some of the most destructive disasters than can hit you, and their toll can reach tens of thousands of deaths and billions of US dollars. If the overall impact of events paints a bleak picture, the personal stories are particularly harrowing. Unlike 2084, these are events which have already taken place and wreaked havoc on the lives and livelihoods of thousands of people. And Powell's personal account of the 1988 Yellowstone National Park fires somehow makes these events more tangible, particularly if you are lucky enough to never have faced such destructive forces.

Powell also addresses issues that have arisen, or could arise, from the responses and management of extreme events. For instance, the action taken by the Army Corps of Engineers to manage the 2011 Mississippi floods could have led to the river reverting to its alternate course, through the Atchafalaya Basin, an event which would have considerable impacts on downstream communities and shipping. Clearly, this did not happen this time, but should we run the risk of causing such a change again, or do we need to think of alternative solutions to manage future problems? Also, during the heatwaves in Europe (2003) and Russia (2010), people lost their lives because they did not know that they had to drink more water in warmer conditions or because they drowned after drinking alcohol. This clearly shows that simple measures, such as awareness campaigns, could yield significant results and allow us to protect ourselves against the worst effects of such events, which helps to address the issues behind 'managing the unavoidable'.

But the overall strength of his argument lies perhaps in the evaluation of predictions made by climate scientists. With rising water vapour levels now observed, is the expected increase in extreme precipitation events already noticeable? It appears so: analyses of US and northern hemisphere precipitation show just this. Similarly, changes in the timing of snow melt, and rising sea-surface and air temperatures have been implicated in wildfires, droughts and heatwaves. But at no point does Powell claim that climate change alone is responsible for all events in recent years. This is particularly true of tornadoes and hurricanes. Not only does he clearly state the uncertainties, he also points out other factors, such as river engineering projects, La Niña and forestry practices, that have played major, sometimes predominant, roles in some of the events he discusses. This is openness at its best, a way of pre-emptively answering those critics who tend to cherry-pick details and miss the whole picture when evaluating climate-related evidence.

So does Powell manage to answer the questions he sets out to answer, namely whether there is now a 'preponderance of evidence' that climate change is under way? He certainly makes his position clear: for him, there is already enough evidence to take action and prevent the worst from occurring. It is difficult to argue against this. Of course, extreme events have always occurred, without the help of humans, but it is the number of recent record-breaking events or worst events in decades that should make us stand up and take note. These come on top of trends that show rising global temperatures, melting Arctic sea ice, retreating glaciers, rising sea levels, and migrating species. All of this is consistent with what we expect from climate change. So do we now wait until we have absolute proof, which probably means leaving it too late to 'avoid the unmanageable', or do we start addressing the root cause of all these changes?

Rough Winds was released as a Kindle Single and is currently at #3 under Earth Science. The good news is that you don't need a Kindle to read it - you can download apps to read it on PC, Mac, iPhone/iPad and Android. With the Horn of Africa and Pakistan experiencing severe drought and floods, respectively, as well a new La Niña possibly on its way, this is a timely book that I thoroughly recommend.

Arguments

Arguments

[DB] See CO2 is not the only driver of climate (Intermediate tab).

[DB] Fixed image.

[DB] If you go to the Posting Tips section, use the html string there with the width 450 limiter in it. Using that string, replace everything between the quote marks with your graphic's URL (in both places).

Use the Preview function to verify the image will appear before posting the comment.

[DB] "I am not sure it has been debunked."

Linear Contrails from aviation have a slight warming effect of +0.01 Wm-2.

Global mean radiative. Anthropogenic RFs and the natural direct solar RF are shown. (IPCC AR4 Section 2.1)

Please do the math and show us how a contrail radiative forcing of +0.01 Wm-2 translates into a reduction in local DTR's by up to 1.8 C?

Until then we will consider it debunked.

[DB] We are left with this: In this absence of actual research or performing the radiative equations (line by line is best) to demonstrate the feasability of your hypothesis, you present unsupported conjecture.

In like fashion, I could be the recipient of a large grant from a Nigerian bank (as I get those email notifications daily), but it remains conjecture until I supply them with necessary bank account details for them to process the deposits (and subsequent withdrawals).

[DB] Do please try to focus more on the topic of this thread: Review of Rough Winds: Extreme Weather and Climate Change by James Powell

You are sounding ever more as one in pursuit of an agenda (denial of climate change and extreme weather) and less as one examining all of the evidence critically. For example, your Black Knight routine after the lack of evidence supporting your position on contrails was pointed out to you, and now you furnish yet another link (off-topic on this thead) in an effort to prosecute your agenda followed on the earlier extreme weather thread.

A greater effort to stay on topic and examining all of the evidence would enhance your position.

[muoncounter] fixed closing link tag