New study offers a glimmer of hope for climate solutions success

Posted on 25 May 2022 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections

The vast majority of climate modeling studies treat human behavior as an external, unpredictable factor. They have projected how the climate would change in a variety of possible greenhouse gas emissions pathways, but have not evaluated the likelihood of those pathways.

That approach informs the public and policymakers about what climate paths they should follow in order to achieve the best outcomes for human society and other species, but it does not provide information about which of the nearly infinite possible paths societies most likely will follow. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses scenarios ranging from less than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) to more than 4°C (7.2°F) warming above pre-industrial temperatures by 2100, but IPCC does not analyze the likelihood of each outcome.

To address that shortcoming, University of California Davis climate economist Frances Moore led a new study, published in the prestigious journal Nature, that incorporated seven social, political, and technological feedbacks into climate models. It’s an effort to assess which human emissions pathways are the most likely.

This approach “is important for adaptation because increasingly we need to give people information about what climate risks are going to look like over the next 50 or 100 years,” Moore said in a phone interview, which is very difficult if scientists are unable to constrain the likely range of human emissions over that period.

The results of the study provide reason for optimism: The Paris Climate Agreement targets remain within reach in about three-quarters of the 100,000 model simulations run by Moore’s team through the year 2100. While significant uncertainties remain, the study envisions a possible future in which a cascade of social and political and technological feedbacks could lead to an accelerating decline in human greenhouse gas emissions.

The human climate feedbacks

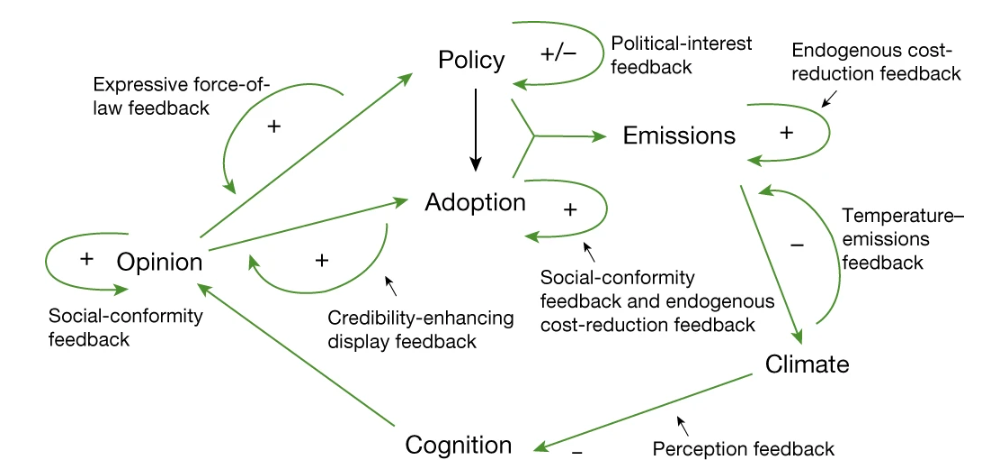

To identify the relevant societal feedback processes that could influence how human greenhouse gas emissions change over the coming decades, Moore and her co-authors conducted a four-day interdisciplinary workshop and a review of literature across relevant fields including social and cognitive psychology, economics, sociology, law, political science, and energy systems engineering. This assessment uncovered seven such climate-social system feedbacks, described below.

The “social conformity feedback” incorporates the influence of public opinion and individual decisions into the model. Public support can often translate into policy changes, with varying success depending on the type of government, and individual behavioral changes can persuade other people to engage in similar actions. For example, if individuals install solar panels or a heat pump or purchase an electric vehicle, those changes can motivate friends or family or neighbors to make similar changes, especially if the individual discusses those decisions with peer groups.

The “climate change perception feedback” accounts for the fact that as climate change and its extreme weather impacts worsen, individuals affected by those events or witnessing the impacts may be more likely to support policies to address the root cause(s). On the other hand, the study authors noted that “several papers have found evidence that interpretations of weather events are filtered through pre-existing partisan identities or ideologies”: As in the analogy of the frog in a boiling pot of water, people may shift their perceptions of what constitutes “normal conditions” as weather gradually becomes more and more extreme over time.

The “political interest feedback,” which describes how policy changes can activate powerful lobbying interests, similarly acts in both positive and negative directions. For example, policies that support renewable energy can bolster the wind and solar industries and their lobbying efforts, but those policies can also trigger adversarial political and public relations activities by powerful fossil fuel interests.

The “credibility-enhancing display feedback” is similar to the individual action component of the social conformity feedback, but it applies to influential individuals. For example, if researchers advocating for climate policies or community ambassadors promoting solar panel installation personally take measures to lower their individual carbon footprints, research has found that the public will view them as more credible, thus enhancing the efficacy of their advocacy.

The “expressive force of law feedback” incorporates into the models that changes in laws and regulations can alter the perception of social norms, attitudes, or behaviors. For example, research has shown that the legalization of gay marriage, smoking bans, and COVID-19 lockdowns had significant effects on public acceptance and norms related to those issues.

The “endogenous cost-reduction feedback” accounts for the fact that as new technologies are increasingly deployed, their costs can potentially fall rapidly as a result of economies of scale, lower input costs, and increased efficiencies that come from the economic theory of “learning by doing.” This effect has been demonstrated, for instance, by the plummeting costs of clean technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels, and lithium batteries.

Finally, the “temperature-emissions feedback” addresses direct impacts climate change will have on the economy. Several studies have suggested that worsening climate change damages may slow economic growth, and given that economic productivity is connected to energy use, this effect could also slow greenhouse gas emissions growth. On the other hand, rising temperatures will increase energy demand for cooling. One 2019 study estimated that these effects combined would reduce greenhouse gas emissions approximately 3% per degree Celsius of warming.

A diagram illustrating how the seven climate-social feedbacks are incorporated into the model and their reinforcing (positive) or dampening (negative) effects. (Source: Moore et al. (2022), Nature).

Results inspire hope, justify cautious optimism

The study authors performed 100,000 model simulations incorporating these seven climate-social feedbacks and then clustered together model runs with similar trajectories of climate policy and emissions through the end of the century. They found that the most common cluster (called the “modal path”), representing nearly half of the model runs, resulted in a most likely warming of about 2.3°C (4.1°F) above pre-industrial temperatures in the year 2100. The second-most common group of simulations, representing more than a quarter of model runs, was categorized as an “aggressive action” scenario in which governments are successful in meeting the Paris Climate Agreement target of limiting global warming to less than 2°C (3.6°F).

They labeled the third-largest cluster “technical challenges,” representing almost one-fifth of model runs. In these scenarios, government climate policies are similar to those in the most common “modal” cluster resulting in 2.3°C warming, but clean technologies remain relatively expensive in light of a weak “learning by doing” feedback relating to the economies of scale, which would slow efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this scenario, global temperatures rise by about 3°C (5.4°F) above pre-industrial temperatures in 2100.

Together, these three scenarios account for nearly 95% of the model simulations, and they all envision many governments enacting climate policies well beyond their current status quo in an effort to meet Paris commitments. Two other clusters labeled by the study authors as “delayed recognition” and “little and late” involve less aggressive government action, as the names imply, but were represented by only about 5% of the model simulations, most likely representing about 3-3.5°C (5.4-6.3°F) warming in 2100.

Global carbon emissions trajectories from 100,000 runs of the coupled climate–social model, grouped into 5 clusters. The line thickness corresponds to the size of the cluster. (Source: Moore et al. (2022), Nature).

Global carbon emissions trajectories from 100,000 runs of the coupled climate–social model, grouped into 5 clusters. The line thickness corresponds to the size of the cluster. (Source: Moore et al. (2022), Nature).

The study did not include the potential for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) from the atmosphere. Incorporating successful CDR on the scale recommended by the National Academy of Sciences and IPCC (approximately 750 billion tons of cumulative carbon dioxide removed by 2100) would roughly bring the warming experienced in the modal path in line with the Paris Climate Agreement target of limiting global warming to less than 2°C (3.6°F). Combined with the “aggressive action” cluster, this leaves about three-quarters of model runs within reach of the Paris targets.

Key factors and caveats

The most influential factors in the model runs were the strength of public opinion, clean technology cost reductions, responsiveness of political institutions, and the role of cognitive biases. Several of these factors tend to act against climate solutions in the United States, with its population heavily politically polarized and government policy not very responsive to public opinion in any event, perhaps due largely to structural status quo biases. But rapidly falling costs have led to clean technology adoption even in many so-called “red” states, and a number of other states have carried out ambitious local climate policies. And in many countries like Canada and across Western Europe, governments have been responsive to public support for climate solutions.

As in any modeling exercise, there are significant uncertainties in the study’s results, related both to physical and social factors. It’s also possible that the study did not include some important negative feedbacks, for example if rising energy prices reverse public opinion support for climate policy, or if highly politicized nationalism or isolationism increases as climate change potentially makes resources increasingly scarce.

Climate modeler Drew Shindell, not involved in the study, also flagged potential unaccounted-for negative feedbacks like media biases, noting, “for example there are loads of reports on EV battery fires (even though they are far less common than gas-powered vehicle fires), which could lead to public opinion being a negative feedback suppressing changes.”

Consilience with cautious optimism from other studies

The study’s bottom line could best be characterized as suggesting that governments might succeed in implementing climate policies starting within the next decade that are sufficient to limit global warming to somewhere between a bit less than 2°C and 3°C by 2100. While this includes a wide range of increments of climate change and associated damages, the results suggest that the most catastrophic outcomes above 3°C are relatively unlikely, with the aforementioned caveats.

As climate scientist and past regular contributor to this site Zeke Hausfather found in a separate Nature commentary published with Moore, numerous recent studies have found that when accounting for implemented climate policies and pledged targets, the most likely temperature outcomes tend to fall in that same 2-3°C range. As Hausfather noted via email, Moore’s new study is “a completely independent way of assessing plausible emissions outcomes … which makes it valuable and its consilience with other lines of evidence noteworthy.”

The new study’s most likely outcome suggests that global emissions will continue to rise over the next 8 years, missing the 2030 Paris pledges, but will decline rapidly thereafter to bring the 2050 targets within reach. For example, increasing public support

- could spur climate policies in many countries,

- which could catalyze the deployment of clean technologies,

- which could drive down their costs,

- which could further increase public support,

- … and so on in a cascading positive feedback effect.

As Moore told Yale Climate Connections, near-term climate failures could make people “way too pessimistic. If there are these spillovers like ‘learning by doing’ effects and cost reductions and network effects, it’s possible to be taken by surprise positively” by accelerating emissions reductions after 2030.

Given ongoing struggles and delays in adopting and implementing climate policies in many countries like the United States, some advocates for climate action may be heartened by this potential hope for success – or at least for progress – in coming decades.

Arguments

Arguments

This study reinforces the understanding that without significant socioeconomic and political system changes the future of humanity will suffer the massive harmful consequences of warming impacts exceeding 1.5 C.

Note that the peak warming and when the peak impact is achieved, not the warming impact by 2100 with more warming to follow, is required to determine the potential required adaptations.

And it needs to be pointed out that the producers of the future problem owe the harmed people of the future (and harmed current day people) significant help by developing adaptations that are sustainable in the harmed future they are creating.

An important systemic change is learning that development that results in increased energy consumption, or any other increased per capita consumption beyond the minimum consumption needed to live decently, is not improvement or advancement. Developments that require less consumption, and that reduce harm done by the consumption (ideally no waste), are needed. And socioeconomic-political systems that will reward and ecourage that (and discourage and penalize the opposite) need to be developed strengthened and maintained.

"Several of these factors tend to act against climate solutions in the United States, with its population heavily politically polarized and government policy not very responsive to public opinion in any event, perhaps due largely to structural status quo biases."

Very true. Its like American politics has turned into a contest between republicans and democrats that exists for its own sake like a sport. Feuds can go on for decades.

Nigelj,

The US polarized politics is like a Sport if one team tried to limit harm done and the other team tried to maximize harm done.

One US team fights any way they can get away with to protect their team's interests from 'restrictions on how harmful they can benefit from being'. They powerfully resist learning to be less harmful.

The other US team also fight against restrictions of harm that their team would benefit from, just not as aggressively as the more passionately harmful team..

That US harmful competitive reality is likely the result of the free-for-all fight for status that is a fundamental aspect of the American experiment in maximizing freedoms. That is an experiment that is harmfully failing but the players won't admit it because that would mean they would have to learn to accept that less freedom is better. They would also have to admit they owe compensation for the harm they have benefited from.

This article talks about "renewables" but makes no mention of the fact that no solar panels are made in the US, all of them come from China. Should the US be totally dependent on China for panels? Also, no mention of nuclear power, which is the most reliable and self-reliant source of power for the future.

louislorenziprince

The article wasn't really getting into a discussion about the merits of different power sources. It was more about how human behaviour can be factored into predictive models. However that might include concerns about reliance on China, and human perceptions of nuclear power, which are generally quite negative in America.

Nuclear power is indeed largely self reliant and does have some merits imo, but it is not a panacea. It has various downsides like high capital costs and its slow to design and build and there is public resistance. But this is not the right page to discuss nuclear power.My point is only that it has positives and negatives that would both have to inform any predictive model

Louis, the solar panel manufacturing situation is quite a bit more complicated than you imply.

Here's a fairly deeply reported story on that:

Which solar panels are made in America? (2022 edition)

Reading all the way to the end, we end up with four manufacturers with all parts created in the US. Many more source polysilicon from overseas, with everything else made in the US. Others are a more mixed bag.

But "no solar panels are made in the US, all of them come from China" is misinformation.

(Not as a slight personally directed to Louis but more as a remark on behavior we all more or less share, it required about 5 minutes to learn what's actually true in this particular situation.)

I think there may be much more than adding a little reason here or a nudge there to have the public match the concerns. IN 2014 SUV's matched sedan sales and in 2019 they doubled those sales of efficient sedans. Pickup sales almost tripled between 2008 and 2019. The sacrificing is not there. No one is turning in thier stockings to make parachutes for this. This voting with thier wallets covers a larger period of time than mentioned, that spans several political administrations, several rounds of political waverings, and many years of warnings. And it represents a direct cancelling of gains by, say, all new EV sales. This indicates a stronger task than just rephrasing the importance, or some new study indicate.

peppers @7,

There is indeed evidence that public perceptions developed due to harmful misleading marketing or a simple lack of concern among richer people are a problem.

The Lincoln MKZ is an interesting case. The luxury sedan had a hybrid model sold at the same price as the non-hybrid model. Yet the hybrid version never exceeded 30% of annual sales.

And there is indeed a pickup popularity problem (that is bigger in Canada and the USA than in other places like Europe).

However, SUVs are not necessarily a serious problem. The serious problem is the over-sized vehicles, particularly the luxury models.

And the fuel efficiency ratings tell the story. My resource for comparing fuel efficiencies is National Resources Canada's "Fuel consumption ratings search tool"

fcr-ccc.nrcan.gc.ca/en

The Lincoln MKZ hybrid model consumption was about 6 litre/100km. The non-hybrid MKZ was about 10 l/100. That significant fuel saving was not enough motivation for the majority of the MKZ buyers.

The comparison of ICE vs Hybrid for general vehicle categories like sedans and SUVs using the Canadian search tool shows the following for 2022 models:

So trucks are a problem. And Hybrid SUVs are potentially worse than Hybrid sedans. But the luxury and higher powered sedans are worse than the best SUVs. And the tiny cars are not necessarily better.