Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Staircase wit. L’esprit de l’escalier. It’s the way the perfect response in an uncomfortable conversation comes cruelly late, occurring only after the crux moment has long since passed, and you’re descending the stairs on your way home.

Why didn’t I think of that? you ask, kicking yourself for temporarily forgetting how carbon isotopes show that fossil fuels are indeed the source of the CO2 buildup in the atmosphere.

As the American culture war flares up like a SoCal heat wave, many feel understandably helpless watching misinformation accelerate throughout society. But even as you hit “enter” on a witty post correcting the spelling and grammar of someone who suggests scientists are incompetent, at some level you probably know this doesn’t improve the situation. Lobbing talking points back and forth typically only entrenches deeply held positions, a process known as belief polarization.

Want to see some expert comeback strategies for discussing #climatechange with a doubter?CLICK TO TWEET

So how then, to respond? Do you nod, smile, and walk away with clenched teeth? Do you whip out your smartphone and wave around graphs of ice core data?

Here are four strategies, each from a distinctly different point of view, each penned by an expert, each useful in either a face-to-face conversation on an online chat. The first lesson is this: have a conscious strategy, rather than a knee-jerk response. Think about where you want to go and what your goals are. And if your aim is to simply make the other person feel bad or look bad, then maybe reconsider if that’s helpful to either of you.

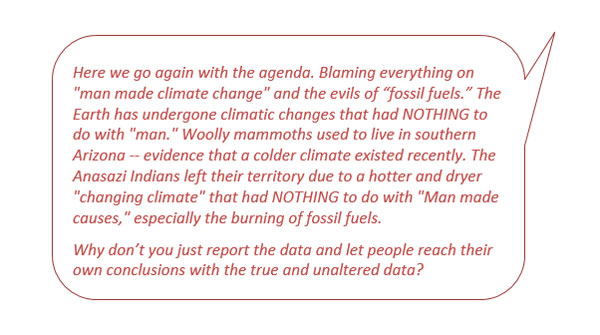

Let’s start with one of the most common climate contrarian remarks of all. One we’ve all heard many times: but the climate has changed before!

This is a modified version from a commenter on a government science agency Facebook page.

This is a modified version from a commenter on a government science agency Facebook page.

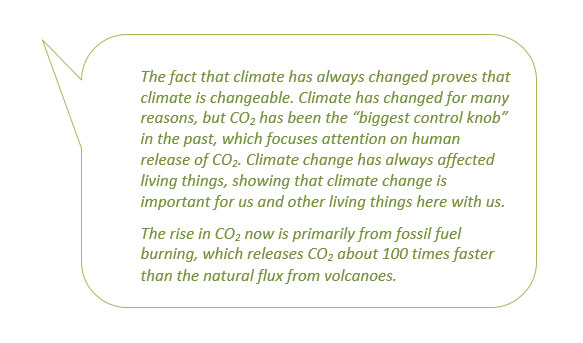

At its core, climate change is a scientific topic, although the controversy around it is largely pinned to ideology, rather than to scientific acumen. Nonetheless, a healthy dose of science is rarely a bad idea, as long as it’s delivered in a constructive manner. Remember, climate contrarians who have changed their minds have credited science more than any other factor.

Richard Alley, a widely respected climate scientist and communicator, host and author of the PBS documentary and companion book, Earth – The Operators’ Manual, and presenter of countless standing-room-only scientific talks, offers his scientific debrief of this common contrarian talking point.

Alley continues with his explanation, noting, “In certain settings, experts have some expectation that they will be allowed to make a long enough statement to summarize the knowledge on which they are expert.”

The savvy communicator, Alley knows that even the best science can fall flat without a personal connection. “Responses must be tailored to the person or persons in the discussion, their demeanor, and much more.” And even fabulous lecturers know that a conversation is more effective than a lecture. Alley looks for a fruitful avenue, “Is there a hint of a question … that could be used to open the discussion?”

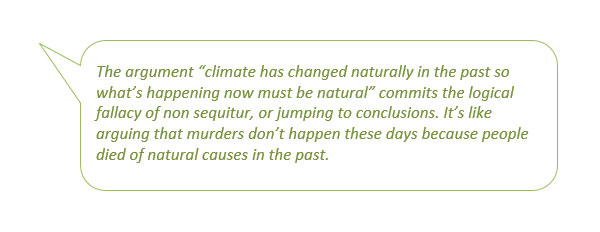

Few may be surprised that most attempts to undermine climate science hinge on some type of misinformation. Cherry-picked data, fake experts, and conspiracy theories are well-worn hallmarks of contrarian rhetoric.

John Cook, founder of Skeptical Science and now a research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, has extensive experience unraveling climate denial. Cook’s work has found that a sort of “inoculation” can help with climate misinformation. In other words, if people are exposed to the techniques commonly used in misinformation, they become more resistant to being misled when in the future they encounter bogus information.

So Cook’s response to the example comment is simple. He points directly to the logical fallacy at the heart of the myth, and uses an easy example to illustrate that the statement can’t be correct.

Credit: John Cook.

Cognitive science suggests that lengthy, complex information is not as memorable as short, sweet takeaways. Cook uses cartoons and analogies to help message resonate.

Cook explains, “The beauty of this type of response is that by addressing faulty logic, you can demonstrate that an argument is false without having to get bogged down in complicated scientific explanations.” He adds, “Although as a science communicator, I’m always keen to explain the science whenever I get the chance.”

Although it’s tempting to be smug when you feel facts are on your side, that’s unlikely to buy you traction. “Discuss the topic with respect, try to understand their thinking and how they came to their position,” advises Cook. And even more importantly, “Recognize that most people who use this argument are also victims of misinformation.”

One of the hardest tasks when faced with someone whose opinions clash with yours is to take a deep breath and do the unthinkable: listen.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

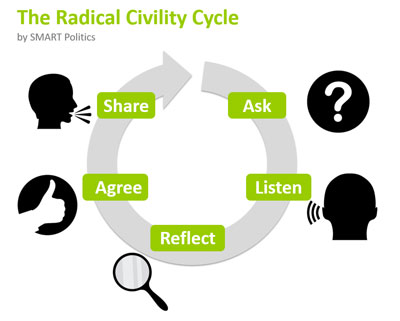

Karin Tamerius, M.D., founder and managing director at Smart Politics, is trained in both psychiatry and political psychology. (Could there be a better preparation to understand today’s politics?)

Tamerius innovated an approach termed Radical Civility, which starts off by asking questions and actually listening to the answers. Radical, indeed.

Note how she starts off by agreeing with the commenter, and then asks a probing question.

“This seems to be a person who cares about and believes in science,” observes Tamerius. “For that reason, they are likely to be responsive to an inquiry about how climate science works.”

The Radical Civility Cycle is not a one-and-done approach. It takes several rounds of questions to establish rapport and nudge the conversation toward a productive outcome. Tamerius illuminates her long-game strategy, “I would hope to learn everything this person knows about the history of non-man-made climate change. Then, once they feel fully heard, I would gently explore the ways in which climate change is different in the human era and how we know.”

In an era where arguing dominates much of our public discourse, this technique offers a refreshing alternative. “I’m trying to move the other person from an argumentative to a learning mindset,” Tamerius notes. “I want them to be motivated by curiosity rather than a desire to show they are ‘right.'”

Scott Gruhn doesn’t have formal training in climate science or communications, but he demonstrates admirable skill in both arenas. Gruhn is a tireless, effective defender and explainer of climate science on Facebook. His persuasive posts routinely get people to soften their stance and consider evidence, and he’s even been able to usher a half dozen people to do a complete turnabout in their views.

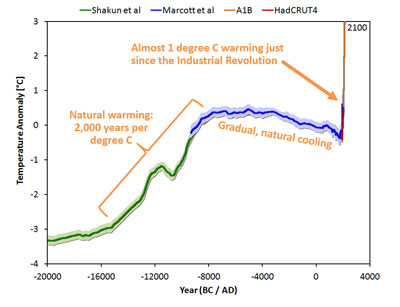

Like Tamerius, Gruhn settles in for a protected exchange, and kicks things off by praising and respecting the point of view of the commenter.

Gruhn continues, often in a series of shorter posts rather than one encyclopedic and unnavigable post.

Base image used with permission.

Gruhn often peppers his responses with graphics, and steps readers through the science in a friendly manner. Here, he annotates a graph for easy comprehension.

Taking a cue from John Cook’s strategy, Gruhn makes a point to shine light on tactics used to spread misinformation. He offers these insights as advice to commenters, rather than beating them over the head with it.

Gruhn’s closing advice is something we can all take to heart, and ring ever more true as we unfriend, ignore, and turn our backs on people with different ideologies.

“Know the science. Know your values. Be caring. Don’t expect dramatic, visible changes of heart. Write for the undecided readers. Turn off the computer before your words get too sharp.”

The author is grateful to John Cook of George Mason University for his advice and recommendations on this project.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 8 August, 2018

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |