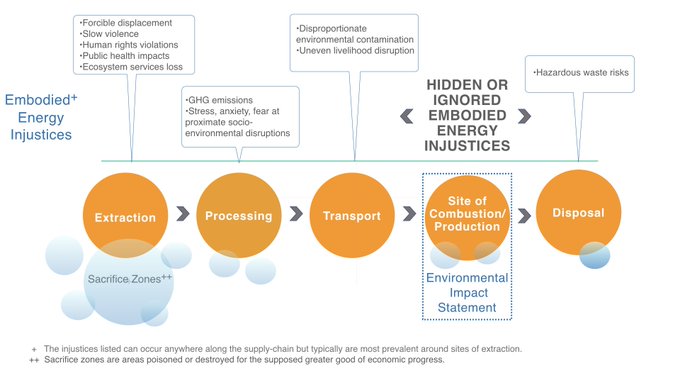

"Embodied energy injustices: Unveiling and politicizing the transboundary harms of fossil fuel extraction and fossil fuel supply chains".

New paper with @jenniecstephens & @stephmalin_soc

Thread (1)https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618306698 …

Blood coal: Ireland’s dirty secret

Posted on 25 October 2018 by Guest Author

Noel Healy (@DrNoelHealy) is an Associate Professor of Geography at Salem State University. He received his PhD from the National University of Ireland Galway. He is a native of County Clare, Ireland.

The connections between County Clare, Ireland and La Guajira, Colombiamay not be entirely obvious at first glance. Yet the regions are linked through a shared commodity: coal. Extracted in one region and burned in the other.

Coal extraction in La Guajira has a dirty secret, which I’ve witnessed first-hand: it is connected to a system of production entrenched in violence, bloodshed and environmental destruction.

Since 2001, almost 90% of coal burned at Moneypoint power station in County Clare in the west of Ireland has come from Colombia. Two-thirds of it was purchased from Cerrejón mine in Colombia’s northern department of La Guajira.

Spanning 69,000 hectares – around three quarters the size of county Dublin – Cerrejón is one of the world’s largest open-pit coalmines. It is also linked to well-documented environmental and human rights abuses for over two decades.

Moral and ethical duty

Ireland’s largest electricity-generation station, Moneypoint, is owned and run by the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) utility company. Because the ESB is majority (95%) state-owned, the Irish government has a duty and responsibility to challenge and try to prevent adverse human rights impacts connected to the company’s fuel purchases.

As the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights put it,

Businesses have a responsibility for human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.

Extraction “sacrifice zones”

I’ve seen the impacts. On two separate Witness For Peace delegations to La Guajira, human rights campaigners and academic researchers, myself included, documented human rights violations and the socio-environmental devastation inflicted on communities in Cerrejón’s mining zone. Our newly published study reveals that inhabitants of La Guajira have become victims of coal mining, instead of beneficiaries. It also reports parallel injustices among communities affected by fracking in Pennsylvania.

Cerrejón mine has displaced thousands of historically marginalised indigenous Wayúu, Afro-Colombian and campesino communities by physical force, intimidation, coercion, and through the contamination of drinking water and farmland. Cerrejón mine uses over 17 million litres of water a day, but the average person has access to just 0.7 litres.

Antonia is an indigenous Wayúu mother. The Cercado Dam drained the Rancheria River, her communities only nearby source of water. Photograph: Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Displacement

Official displacement follows a Colombian legal procedure called “expropriation,” where the state approves or participates in the removal of populations in zones designated for natural-resource extraction or megaprojects. But the involvement of the Colombian government does not necessarily make the displacements just or nonviolent.

In 2001, for example, the Afro-Colombian town of Tabaco was bulldozed and its residents forcibly removed by state security forces to allow the Cerrejón mine to expand. A Colombian Supreme Court order called for the community to be resettled. Following an independent inquiry in 2008, Cerrejón mine signed an agreement for the reconstruction of Tabaco. Ten years later, Tabaco residents have yet to be resettled.

Assassinations of social leaders

In the neighbouring department of El Cesar, three Drummond mine union leaders were murdered in 2001. More recently in La Guajira, activists who resist Cerrejón’s expansion plans have received renewed death threats.

Despite the 2016 Colombian Peace Agreement, there has been a spike in assassinations of social leaders nationwide. At least 123 were murdered in the first six months of 2018.

Arguments

Arguments

Good article, fracking is no answer to climate change. But Ireland does appear to have a modest carbon tax here and here.