Welcome to the Pliocene

Posted on 10 August 2018 by John Mason

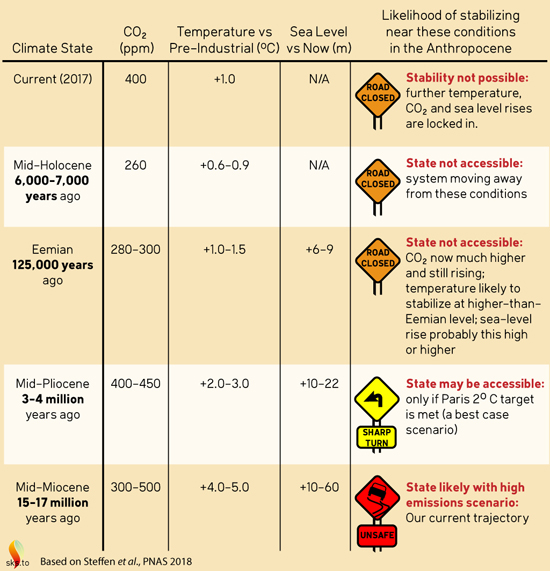

The whole story in a table....

The graphic below (click on it for a large version) is adapted from a table in the supporting information from a newly published paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, as the paper is entitled, looks at several climate states - the present day, the mid-Holocene, the relatively warm Eemian interglacial and, heading back a bit further into geological time, the mid-Pliocene and mid-Miocene. Data are from palaeoclimate studies. The right-hand column assesses our chances of stabilising our climate at these states in the coming decades. In some cases, it is already too late - we have gone beyond the physical parameters that support such climates:

Data details: atmospheric CO2, temperature anomaly relative to the pre-industrial era and sea-levels relative to now measured and from palaeoclimate records. The graphic, created by "JG", is adapted from Table S1 from the paper's supporting information section, available here. Data sources are fully referenced.

Why is this paper important?

Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, written by Will Steffen together with a large interdisciplinary team of colleagues, was published on 6th August in PNAS and has made quite an impact. Certain sections of the media used terms like "runaway global warming" in their headlines, which could be taken by some to imply that the paper says we are going to take Earth to a Venus-like state (it doesn't and we aren't). In fact, the term "runaway" does not appear, either in the main paper or the supporting information, as a quick word-search will demonstrate. However, the possibility that we may nevertheless end up on an unstoppable path to a Hothouse climate-state is something that cannot be ignored. The authors describe examples of how such trajectories could occur, in the main body of the paper.

Hothouse in fact describes Earth's climate state throughout much of geological time, especially in the Phanerozoic (541 million years ago-present day). Icehouse climates, during which glacials and interglacials alternate, are relatively uncommon along the time-line and were often short-lived (in geological terms, that means a few million years). The big problem we have is that we happened to develop as a species during an icehouse climate, and especially during a relatively stable interglacial - the Holocene - during which we have created a widespread high-tech and interdependent infrastructure (i.e. civilisation as we know it), much of which is rooted to the ground. A transition, over the coming centuries, towards Hothouse essentially means an ongoing battle with us on the one side and changing weather-patterns and rising seas on the other, until there is no more Polar or mountain ice left to melt. Chaos, in other words.

Through our activities, especially our intensive burning of the various fossil fuels, CO2 levels in Earth's atmosphere have changed from the 180-300ppm range of the glacial-interglacial cycles, to more than 400ppm, a concentration last seen in the Pliocene. The Pliocene was the period of geological time immediately prior to the onset of the glacial-interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene. Beginning 5.33 million years ago, after the Miocene, and ending 2.58 million years ago, the Pliocene featured a notable period of warmth around the middle of the period, during which boreal forests flourished in the Arctic (see this post from 2013 to learn how that was discovered).

Mid-Pliocene Earth and its climate are of particular interest, because global continental configurations were remarkably similar to those of today. We therefore know that a 400ppm CO2 world, with a near-identical geographical layout, is eventually a much warmer one than the Earth which we are familiar today: it takes time for the planet to catch up - head towards equilibrium with - such atmospheric changes. As the table shows, though, we have taken the atmosphere well beyond anything closely resembling the interglacial-glacial cycles, so that it is towards the mid-Pliocene climate we are, decade by decade, heading. It is the past, not climate models, that is speaking out here. Geological evidence should never be ignored, because it tells us what actually happened.

If we drastically cut emissions right now, Earth will gradually come towards equilibrium with that 400ppm atmosphere (or with whatever CO2 level we end up with). There will of course be consequences in the long term as the table shows, with respect to changing weather-patterns and sea-level rise. However, fail to accomplish such cuts and we risk setting in motion various chains of events that will lead us towards that Hothouse state: some of these chains, referred to in the paper as "tipping cascades", may not be stoppable. Although it's been a hot few months in the Northern Hemisphere, the mid-Pliocene was a bit similar: this is something we may have to get used to. But, "let's not make things any worse", sounds like an extremely good idea to me, right now, bearing in mind that our species has never had to deal with the Hothouse climate state.

Arguments

Arguments

We need to drop all scenarios that start with "if we drastically cut our emissions immediately..." We are not going to drastically cut emissions. It would be a miracle if the world's emissions plateaued. Most likely we will keep pumping CO2 into the atmosphere until the last SUV runs out of gas....

Thanks, John Mason and "JG," for a very clear explanation of the important paper by Steffen et al. It really does seem we're on our way to the Pliocene. The question, as raised by Steffen et al., is whether we can stop there. Some feedbacks will be beyond our control. For a frightening worst-case scenario of what might happen if we continue blindly along the path of business as usual, read James Hansen's forecast of what the Earth might look like in 2525 (pages 260-270 of Storms of My Grandchildren).

Welll, here's another thought, albeit speculative.

No other species has been able to remove barriers to exponential population growth. The human population grew at a glacial pace until the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution detonated the plodding circle of history. For a hundred thousand years, there were fewer than 100 million of us, then about a thousand, fewer than a billion of us. For the last one hundred years, our numbers have exploded.

Like other animals, we're territorial. We want territory because we need some, and we want more because we want it, and if you give up half of yours others will take it, surround you and then take the rest. That is how humans have always been and always will be.

So probably we're headed towards a tipping point, not soon (well over 50 years forward) but inevitable, where people go to war over land and water, then continue wars because fire has its own force.

If Climate Change causes a collapse in feritily, then a decrease in population, we'll avert that scenario. World population falling by, say, 2/3rds would free up massive amounts of land for reforestation, it would decrease the massive amonut of fuels used for farming and it would allow societies to move to accomode rising seas. It would also allow for sharp cuts in C02 output, since when one is not in a war for survival the option to act about other things exists.

Climate change will bring immense costs and eventually destroy coastal cities - that's most great cities - which have been settled for thousands of years. It might also save us from something much worse.

"Most likely we will keep pumping CO2 into the atmosphere until the last SUV runs out of gas...."

Changing your 5000# resource guzzing "suv" for 3400# resource guzzling Prius will do zero of substance to change matters. If you stop eating food, living in a heated building, traveling over paved roads and having kids, it would.

Here's your green car saving the environment:

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/aug/24/nickel-mining-hidden-environmental-cost-electric-cars-batteries

oops, previous comment needs editing, but cannot be edited once posted.

Driving By @4 &5, it's hard for me to see climate change impacting fertility. We know widely available contraception, better women's rights, and reasonable but basic health care appears sufficient to lead to small families, from experience in a couple of African countries. It's hard to see climate change altering this too much. Countries don't need to be wealthy to have lower fertility rates.

Of course bending the population growth curve down with good social policies is all for the good on numerous levels. Middle range projections have population hitting 10 billion by 2100 then slowly declining. Refer population growth projections on wikipedia.

Climate change will increase mortality, but my guess is not enough to lead to actual absolute declines in population numbers, or this would at least be a slow process to develop. Of course catastrophic climate change is a possibility. This would all be a negative feedback, but there are much gentler ways of reducing population size, simply by encouraging smaller families and the magic number is 2 children in western countries, and 3 children in poor countries.

I dont think the nickel content of electric cars makes them any less effective at reducing emissions. It's more a problem of the availability of supply of nickel, and the terrible conditions in the mines. We will probably end up mining old land fills, but this will be true for all sorts of products ultimately.

To keep going on like a broken record, we should abandon all our disparate campaigns and focus on the prime mover. WHO PAYS THE PIPER CALLS THE TUNE. As long as vested interests are allowed to support our politicians, our politicians will do their bidding. Get this one sorted out and all the other very necessary campaigns will suddenly start to gain traction. We are doing remarkably well despite our politicians but no where near fast enough. Just imagine if they were on our side.

As this is your first post, Skeptical Science respectfully reminds you to please follow our comments policy. Thank You!

The biggest issue is that people don't want to give up what they have and why should they! There are lots of 'tips' to save energy and most notably energy saving light bulbs! But what you save in electricty you will spend on a new coat. Everybody has an energy pie which comes from their income and must be spent at all costs, it would seem. Mother nature has saved up all that lovely oil, etc for us to spend and she is the only 'person' to stop us as governements are far too inaffective. I think Mother Nature is starting to get just a little cross withymankind!

I live in Holland and we have the most to lose from sea level change (except Bangaladesh amongst others) but all new cars have airco most people use driers and Sunday roads are always clogged with people tooing and frooing.

If the Ducth who are a very sensible people can't ditch their wasteful habits who can? Interestingly the Swedes are starting to think about taking things more seriously after their wild fires.

https://www.thelocal.se/20180724/swedens-wildfires-are-everyones-business

Ok so ther's a political twist but then again there usally is!

That greenhouse gases and heat energy added to global systems have surpassed those required to bring about conditions similar to the Eemian is already a potential disaster. Return to the environmental conditions of that warm era will disrupt food production in the Midwest USA and similar latitudes in Eurasia. Much of the world population depends on food imported from these most productive of agricutural regions. Pliocene conditions will almost certainly result in famine, and this seems to be the best we can hope for? Personally, my hair is already on fire!

Paleontologists from the Illinois State Museum have found alligator teeth in Eemian deposits just south of St. Louis, Missouri. That's the middle Mississippi valley not the deep south. In an excavation of Eemian deposits on the uplands to the east, near Springfield Illinois, excavations recovered remains of a giant tortoise, similar in size and morphology to those of the Galapagos Islands. Pollen from the associated sediment indicates the local environment was a warm parkland, a mosaic of groves of trees interspersed with open glades.

Alligators can protect themselves in cold weather by surrounding themselves with water or burrowing into rotting vegetation. No such escape for giant tortoises in the uplands. Temperatures in the winter must have been considerably warmer than historic times in which 3 or 4 months of bitter cold have been the norm. Cold snaps lasting more than a few days would have been fatal to the tortoises.

The sites mentioned are within the southern part of USA's "Corn Belt" famed for it's rich black prairies soils and massive production of maize corn and soybeans. The fertility of the soils here is in large part a happy result of our cold winters. When the ground freezes microbial activity ceases as does burrowing activity that increases aeration and oxidation. Under Eemian climate conditions, let alone those of the Pliocene, soils and crops alike will be out of equilibrium with the new environment. In the minds of most soils are considered rather inert. People will be surprised by the rate at which fertility declines.

Since the environment here is optimal for the crops grown, any change in weather during the growing season is likely to be detrimental. Long droughts are a distinct possibility, but if weather swings in the opposite direction, increased rainfall can also devastate crops. In hilly areas erosion becomes a problem. In the more typical extensive flat lands water is slow to move off. Many fields require extensive systems of buried "tiles" to ensure drainage (plastic pipes nowadays). Even 3 or 4 days of standing water kills crop plants.

Just the relatively minor variation in climate through the Holocene has seen the USA's Midwest evolve from near total forest cover to approximately 2/3 tall grass prairie. During the warmest part of the Holocene grasslands extended 100s of kilometers eastward, across the state of Indiana and on into Ohio. All this with changes in temperature and rainfall that were but a fraction of what is already "in the pipe"!

The next dozen years are going to serve up repetitions of the heat waves, droughts and floods (sometimes in the same suburbs in the same month ie Greece) sufficient to bring climate up-close and personal to the average person on the street. That has to happen for humans to pay attention to a threat. It can't be distant, it can't be theoretical. We didn't evolve a mechanism to handle that.

It is socialized, not genetic, this concern for future generations. So most people have difficulty with it. Georgia without Peaches, or a table without food on it, can get our attention.

Homo Sapiens may be an oxymoron but we manage to panic efficiently enough once it is too late to do much... still.. what can be done will be done after the 2x4 events Mother Nature is swinging at our "heads of state" get everyone's attention. So we won't burn it all. We WILL stop burning it sometime in the next dozen or so years, in an orgy of panicked reaction. Too little too late to prevent a lot of damage, but enough soon enough I think, to make that sharp turn.

Maybe. At this point one expects it to be a compound radius "Fishhook".

There will of course, be criminal trials for some, should they live long enough to stand trial.

The Republican Party of the US will disintegrate or reorganize around its cadre of sane "small government" realists. Small government IS a valid goal to continuously strive for, but to paraphrase Einstein "...but no smaller", it has to be at least large enough to do its job.

So not too late, and not hopeless but damnably bad news for us humans. We have to survive long enough to evolve our social structures and select for civilization... and we may not remain civilized long enough to do that.

We will soon see in the upcoming USA midterm elections if this issue can help refocus the country on existential evironmental threats !

BChip @11, I can relate to much of that. Humans are indeed not hardwired to think and act very long term and also think altruistically long term. We are programmed to react strongly to immediate threats which activate our adrenalin system.

We conceptualise and moralise about very long term multi generational threats, but the motivation for action is not as high on a gut level. We do think of our children, but tend to rationalise that they will find a way to deal with the problem.

Having said that, some people do think long term. James Hansen for example. It's always possible to influence people to open their eyes a little. We are a species governend by innate instincts, yet we are not a complete slave to them either.

In fact many people want to see something done when you look at polls, but frankly the political right have neutralised efforts at carbon taxes and meaningfull deployment of renewable energy, and have abandoned any commensense in their world view. Commonsense would suggest medium size government to me, and I think extremes beyond this in either direction are unwise.

It's also not entirely economically rational to expect people to make huge self sacrifices, regardless of the price future generations pay. The system favours fossil fuels and cheap petrol powered cars, and until politicians bend the system to favour renewable energy, it's hard to expect individuals to do too much, although theres no excuse for financially well off people to do nothing.

So yes, because of all this it may take a few more heatwaves to motivate people. I think we are going to end up in damage limitation mode, doing what we can.

trstyles@10: Interesting stuff about the Eemian in Illinois. I live in St Louis and grew up in southern Illinois. I'd love to read more about these alligators and tortises. Do you have a link?

@nigel, #6

I certainly hope the scenario I outlined doesn't become real, and somehow the entire world decides to act reasonably about a condition whose effects are mostly (not all, I know) far in the future. History has far more examples of entire civilizations stumbling into tar pits than it shows them correctly identifying, then planning for and avoiding a future hazard. It's been done - the Dutch and the sea - but it ain't the average.

Driving by @15, yes history is littered with examples of civilisations collapsing due to environmental problems ( Jared Diamonds book Collapse covers some examples) although improving understanding of science allowed us to recognise and fix the ozone hole problem. Of course the industry lobbying was on a smaller scale to fossil fuels, and it didn't so directly affect the public and become politicised. However it shows what can be done with policy when we want to.

I was wondering about the Dutch. They did react well to the problem of sea level inundation, and I guess it was partly because it was so very visible and present, and partly because so much of their land is below sea level that they had no choice. It's just that little bit easier to rationalise that people can migrate inland to escape rising seas.

Fascinating post and discussions. Can someone speak to the rate of the climate changes under the Eemian and Pliocene relative to what’s happening now. These were changes spanning thousands of years. How different will this be, given the relative speed of this change. What will my grandchildren, who would be in their 90’s by 2100 experience with a 2°C rise? How many generations down the line to see the full effects.

Maybe a couple alligators or giant tortises showing up near Springfield, Ill. Now would get denialist politicians attention.

[DB] I'm sure that other contributors will weigh in, but as a general note, the maximum rate of change in CO2 concentrations from the ice core records is about 100 ppm over 10,000 years (around 1 ppm per century).

The current rate of change in CO2 concentrations, OTOH, are about 1 ppm every 20 weeks.

Now set in motion, SLR from land-based ice sheet losses will continue for literally millennia after the cessation of the burning of fossil fuels.

Johnboy, my understanding just as a layperson (more or less) is the pleocene was about 2-3 degrees warmer than today, with sea level about 20 M higher, but this developed over thousands of years. CO2 concentrations were similar to today and changes were slow.

We are forcing change more rapidly, but its a case of how this works out in our reality. On business as usual CO2 emissions we are on track for 4 degrees by 2100 which are Pleocene like temperatures, but because some of the positive feedbacks are so slow, over millenia we could experience temperatures in excess 4 degrees ultimately. Even if we dont hit 4 degrees by 2100 we will get there eventually as positive feedbacks work.

So huge areas of our planet could move to a tropical climate and heatwaves would be on top of that and probably in some of our lifetimes or over the next few centuries after this .

It would take thousands of years for sea level rise to increase to 20M. Ice melts at a certain rate. We would adapt but there is obviously huge loss of land area and soils, and soils take practically forever to develop.

However the thing that gets my attention is evidence within these early climates like the pliocene and others is that there were relatively short periods of rapid warming of several degrees per century, and rapid sea level rise of 2-5 m per century, something we would have huge difficulty adapting to. There's also evidence of things like super storms and abrupt climate shifts in the atmospheric and ocean circulations which have huge regional implications.

If sea level rise was 20 metres over thousands of years we would adapt to some extent, but rapid sea level rise of more than 1 metre per century, for maybe a couple of centuries would be catastrophic and much harder to adapt to. Theres already evidence of a speeding up of ice melt in Antractica as a whole, including both east and western glaciers.

The pleocene world.

On the topic of adapting to SLR, I came across this 2014 PNAS paper, Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. From the abstract:

Can I interest anyone in an un-elevated bayfront house in Hampton Roads? My brother expects to sell his (so far) perfectly good house as a teardown, and the new owners to build a new, elevated one. He's adapting to SLR by moving 15 ft. uphill!

Johnboy, in very broad brush terms, the change from glacial (22k ybp) to warm (10k ybp) is 4-5 degree C. ie 0.04 degree per century compared to around 0.6-0.8C per century now. However, that is a very smoothed rate of change in a somewhat spiky record. There were short periods of faster warming/cooling especially in polar/temperate regions of both hemispheres (but not necessarily in phase), eg Younger Dryas, Antarctic Cold Reversal event etc. However, unlike the transition from glacial, the rate of forcing is also much higher as DB has said.

@ Johnboy - the fastest major sea-level rise that we know about was the one approximately 14,500 years ago, known as Meltwater Pulse 1A. This involved up to 20m change in up to 500 years - or roughly 4m per century: however, its detailed progrssion is still the subject of much research.

Just to clarify my rushed comment @18 where I said that sea level rise of 20 m would take thousands of years as ice melts slowly, but I mentioned periods of rapid sea level rise in apparent contradiction to this. The periods of rapid sea level rise appear to relate to very strong regional warming in critical areas of the Americas, and destabilisation of glaciers causing their flow to speed up.

Meltwater pulse 1a has its own wikipedia entry and it's quite good.

is there a simple elevator answer to a question why was the mid-holocene 0.6 to 0.9 degrees warmer than the pre-industrial (if I'm reading the chart right) when the CO2 was a bit lower (260 ppm vs 280 ppm)? ... less volcanoes?

as a supplementary the mid-holocene sea level vs now is shown as N/A which I understand to mean not-applicable probably (I'm guessing) meaning the difference was < 1 metre, but do we have any more precise idea what it was? — I'm guessing lower than now because it wasn't quite as warm, but by an amount < 1 metre , or by an amount within the range of error so we don't really know more than it was about the same (I recall somone'e lecture about Roman fish tanks implying sea level about the same as now)

Orbital forcing peaked in the early Holocene and has declined since. Less energy went into melting ice, and into warming the oceans, slowing the rate of ice sheet mass losses and slowing the rising of sea levels.

Larger Image

Typically, when climate scientists try to understand some of the expected future effects of global warming and climate change, they first look to the past. And in looking to the past, we can use the example of the climate transition from the icy depths of the Last Glacial Maximum into our current Holocene Interglacial to guide us. From about 21,000 years Before Present (BP) to about 11,700 years BP, the Earth warmed about 4 degrees C and the oceans rose (with a slight lag after the onset of the warming) about 85 meters.

However, the sea level response continued to rise another 45 meters, to a total of 130 meters (from its initial level before warming began), reaching its modern level about 3,000 BP.

This means that, even after temperatures reached their maximum and leveled off, the ice sheets continued to melt for another 7,000-8,000 years until they reached an equilibrium with temperatures.

Stated another way, the ice sheet response to warming continued for 7,000-8,000 years after warming had already leveled off, with the meltwater contribution to global sea levels totaling 45 additional meters of SLR.

Which brings us to our modern era of today: over the past 100 years, global temperatures have risen about 1 degree C…with sea level response to that warming totaling about 150 mm.

Recently, accelerations in SLR and in ice sheet mass losses have been detected, which is what you’d expect to happen when the globe warms, based on our understanding of the previous history of the Earth and our understanding of the physics of climate.

Bigger Image

Sources for my SLR commentary: