A Powerful El Niño in 2015 Threatens a Massive Coral Reef Die-off

Posted on 13 August 2015 by Rob Painting

- A powerful El Niño event continues to strengthen in the Pacific Ocean. During El Niño the poleward transport of warm surface water out of the tropics slows down dramatically and generally results in anomalous short-term heating of the tropical ocean - home to the world's coral reefs).

- Because of the long-term warming of the oceans by industrial emission of greenhouse gases, the temporary surge in tropical sea surface temperatures associated with El Niño now threatens large-scale coral bleaching episodes - times when the maximum summer water temperatures become so warm that coral die in large numbers.

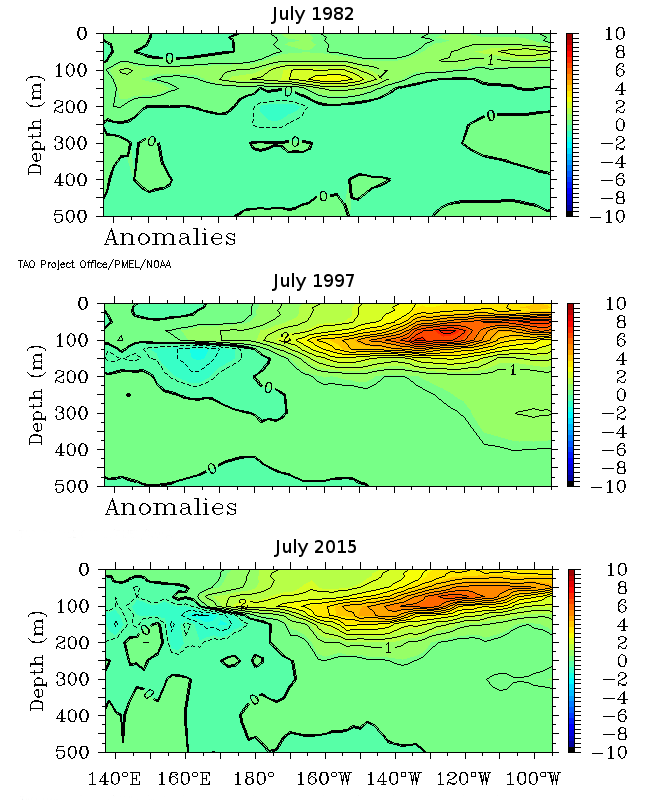

- The powerful El Niño now forming, combined with the ongoing ocean warming, suggests that we are likely to see a mass coral bleaching episode that approaches, or exceeds, the large-scale bleaching that came with the Super El Niño years of 1982/1983 and 1997/1998. The 1997/1998 Super El Niño saw 16% of the world's coral bleach, the largest die-off ever observed, and some of this coral has never recovered.

Figure 1 - Coral bleaching outlook for August-November 2015 based on climate model forecasts. The figure is a from an new experimental product at NOAA's Coral Reef Watch.

Some Don't Like it Hot

The great irony of ocean warming and coral is that, until the late 20th century, it was actually beneficial to coral growth rates. Now, however, warming of the tropical ocean has progressed to a point where natural fluctuations of water temperature over summer months can now exceed an upper thermal tolerance threshold and which can often result in the death of coral reef communities. This is commonly known as mass coral bleaching, and takes place when coral have been subjected to water temperatures 1-3 degrees celsius above the normal summer maximum for several weeks or more.

Figure 2 - an example of coral bleaching. The loss of coloured pigments produced by the symbiotic algae makes the white coral skeleton visible beneath the coral polyp's translucent skin tissue. Image from NOAA's Coral Reef watch.

Coral reefs consist of colonies of individual coral polyps which build their skeletons together so that they form massive structures capable of providing habitat for hundreds of thousands of marine species. Symbiosis is the term which describes the mutually beneficial relationship between the coral polyp and photosynthetic algae that live within its skin tissue. Through photosynthesis the algae provide food, in the form of sugars, to the polyp and also boost its immune system. In return the polyps provide safe lodgings for the algae. When this relationship breaks down, as it can do for a number of reasons but especially so when water temperature becomes too warm, the coral polyps expel the algae. Because the algae produce the pigments which give coral its colour, the loss of the algae results in the white coral skeleton becoming visible through the polyps transparent skin tissue - it appears to have been bleached.

Given sufficient time, most reefs can re-colonize areas that have been killed through bleaching, although some areas in the Galapagos Islands have never done so. But the issue with a warming ocean is that, eventually, the frequency and severity of bleaching will become so intense that coral reefs never recover (Hooidonk et al [2013]).

El Niño & Mass Coral Bleaching

The majority of the incoming energy from the sun is received in the tropics, however not all of this energy is able to be radiated back out to space at the top of the atmosphere - there's a surplus. As one moves away from the tropics toward the poles, a point is reached where the Earth radiates away more energy to space than it receives from the sun. If the tropical atmosphere and ocean are to avoid relentless warming day-after-day they need to shed the excess energy, and they do so by moving the excess poleward (meridionally) in giant loops or cells in the atmosphere and ocean. The circulation within the ocean, where heat is transported out of the tropics, is called a subtropical cell. In this cell water upwells at the equator, travels poleward at the surface, submerges at the centre of the subtropical gyres and then returns back to the equator below the surface, thus completing the circuit.

Figure 3 - The latitude-depth section of average ocean temperature and meridional streamfunction (north-south ocean current) at 170 degrees west. The north-south transport at the surface is complemented by a return to the equator below the surface. Image from Nonaka et al (2002).

The tropical trade winds, which blow from east-to-west near the equator, are the key mechanism in powering this subtropical ocean cell. When the winds strengthen, as they do during La Niña, not only is more heat is buried beneath the surface in the western tropical Pacific, but the subtropical cell spins up and transports a greater-than-average volume of heat out of the tropical ocean in the surface layers. Cold water upwells to the surface at the equator to replace it. With El Niño the opposite occurs; the weakening or reversal of the trade winds means not only is heat transport out of the tropical surface ocean reduced, but so too is cold water upwelling at the equator. The weakened trade winds also allow the heat buried in deeper ocean layers in the west to surface and, as this bulge of warm water relaxes under the pull of gravity, to become smeared out across the Pacific. The temporary rise in sea surface temperature associated with these processes is why we now see mass bleaching episodes when El Niño arrives.

A Warm Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation Phase is Set to Intensify Coral Bleaching

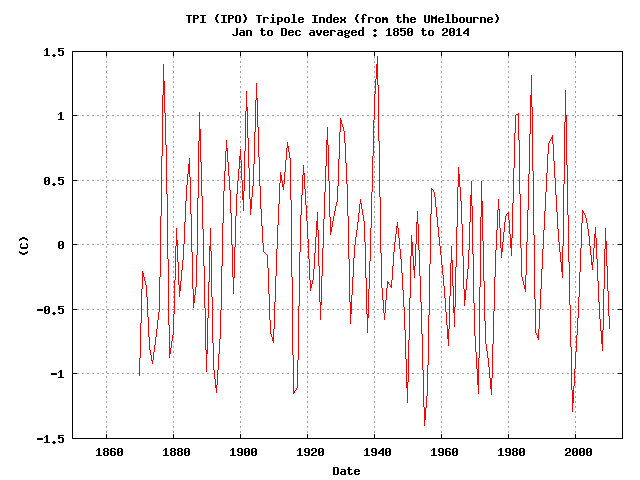

The Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) is a natural variation in the Earth's climate taking place over decadal timescales. In the cool (negative) phase La Niña is in the ascendancy, and during the warm (positive) phase El Niño is dominant. Following on from the earlier explanation of the spin-up and spin-down of the subtropical cell, we can see why there have been a number of mass coral bleaching events in the late 20th century, but few in the 21st century despite the strong warming of the ocean. From 1999 to 2013 the Earth's climate system has been under the influence of the cool phase of the IPO - a time of La Niña dominance. Trade winds over this time have been very intense (England et al [2013]), so the export of warm surface water out of the tropics, and upwelling of cold water at the equator, have been intense too. Before that (1976-1998) the warm IPO phase prevailed and coral began to experience bleaching as their upper thermal tolerance threshold was exceeded during the strong El Niño events of that time.

Figure 4 - The Tripole Index records the state of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). Positive values indicate an El Niño-like state and negative values more La Niña-like. Image from NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory.

Figure 4 - The Tripole Index records the state of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). Positive values indicate an El Niño-like state and negative values more La Niña-like. Image from NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory.

In the last 18 months or so it's looking increasingly likely that the IPO has reversed once again and we are in the early stages of the next IPO warm phase. We won't know for sure until a year or two more, but if this is correct then the ascendancy of El Niño is going to cause serious trouble for coral reefs. Mass bleaching events were associated with the Super El Niño years of 1982/83, and also the Super El Nino years of 1997/98 - where around 16% of the world's coral bleached. The upper ocean has accumulated a great deal more heat since the 1990's and this warming is likely the reason why the moderate El Niño of 2009/2010 saw the 2nd largest bleaching episode ever recorded.

A Bleach Future

The magnitude of the El Niño now taking shape in the Pacific suggests the 2009/2010 bleaching episode will be exceeded, and maybe even the bleaching associated with the Super El Niño of 1997/1998 too. This coral bleaching episode will play out over the next year as El Niño is discharged and the anomalous heat, now confined to the equator, moves to other parts of the tropical ocean, but don't be surprised if it's one of the worst coral reef die-offs ever observed.

Figure 5 - Equatorial Pacific Ocean temperature anomalies for July in the Super El Niño years of 1982 & 1997 as compared to the same period in 2015. Images adapted from NOAA's TAO Triton.

Arguments

Arguments

Thanks, Rob! A very interesting, informative discussion! There's a missing piece of information, however--the horizontal scale for Figure 5. My guess is that the scale should be degrees longitude, at the Equator, across the Pacific, but my guess may be totally incorrect. What should the scale be?

[Rob P] - Thanks Joel, I inadvertently deleted the information when making that image. I'll fix it later today - I've amended the caption in the meanwhile.

EDIT: Now fixed.