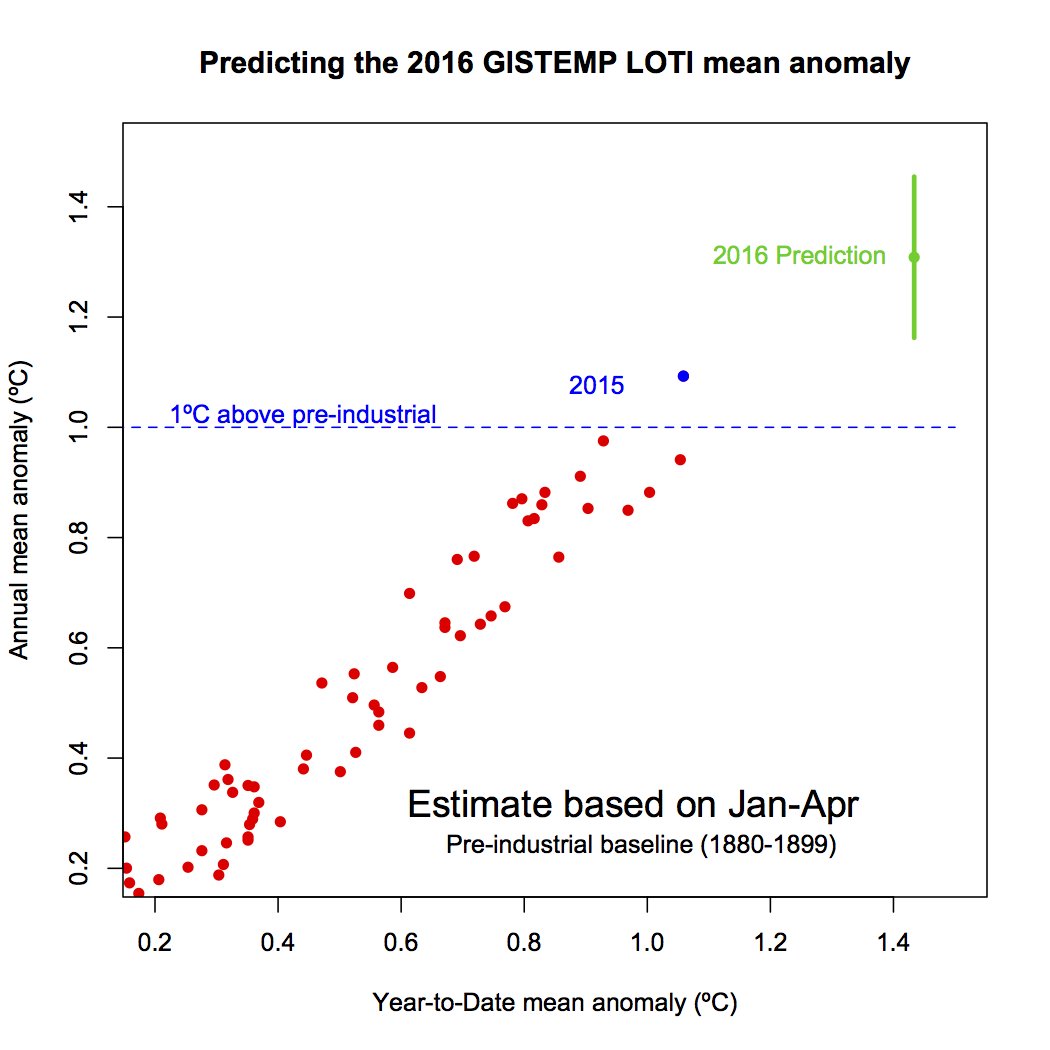

With Apr update, 2016 still > 99% likely to be a new record (assuming historical ytd/ann patterns valid).

Scientists: 2016 likely to be hottest year on record despite looming La Niña

Posted on 7 June 2016 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Roz Pidcock

The phenomenon known as El Niño, which combined with human-caused warming to supercharge global temperature in 2015/16 and brought chaotic weather worldwide, is officially on its way out. But stepping quickly into El Niño’s shoes is its cooler counterpart, La Niña.

Carbon Brief has been speaking to climate scientists about what it all means. Despite La Niña’s propensity to drag down global temperature, so exceptional is the warming we’ve seen so far this year that 2016 is still likely to top the charts as the hottest year on record.

But we should expect 2017 to be cooler than 2016, as the world begins to feel the full force of La Niña, scientists say.

El Niño is over

The El Niño that left such a mark on weather, crop yields and water supplies in 2015/16 is firmly on its way out. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology this week became the first of the world’s major weather organisations to officially declare it dead.

The high sea surface temperatures that have characterised the equatorial eastern Pacific Ocean are waning and relative calm is on its way to being restored, say scientists.

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region relative to 1981-2010 average, showing a drop-off in the last five months. Anomalies equal to or above +0.5C characterise an El Niño. Source: NOAA ENSO blog.

This El Niño was no ordinary event. Prof Adam Scaife, head of monthly to decadal prediction at the UK’s Met Office, tells Carbon Brief:

“The recent winter peak of El Niño was a near-record event, and the strongest El Niño for nearly 20 years.”

The departing El Niño rivalled the massive 1997/8 event as the strongest on record and it was unexpectedly tenacious, says Prof Kim Cobb, whose work at Georgia Tech University involves reconstructing past temperatures in the tropical Pacific using corals. Cobb tells Carbon Brief:

“I’ve been surprised at how long this El Niño event has lasted. Central Pacific sea-surface temperatures were still ~1C warmer than average through late April.”

The El Niño is now dissipating at quite a pace. This part of its behaviour is not so unusual, says Prof Mat Collins, joint Met Office chair in climate change at the University of Exeter. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The transition to neutral/slightly cool conditions has been quite rapid, but the large events do tend to die-off rapidly in this way.”

So, what happens next?

‘Switcheroo’

While the record-topping El Niño may be fading fast, hot on its heels is its cooler counterpart, known as La Niña.

During La Niña, a change in the trade winds mean more heat is absorbed from the atmosphere into the ocean than usual. In El Niño years, the reverse happens and more heat enters the atmosphere from the ocean instead. This major reshuffling of heat means both El Niño and La Niña tend to have big – but opposite – effects on global surface temperature.

Most climate models predict a return to neutral conditions during 2016’s Northern Hemisphere summer, before tipping the balance the other way into a full-blown La Niña.

The chance of a La Niña developing before the end of the northern hemisphere winter is 75%, according to scientists at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Models put the chance of La Niña developing during the Northern Hemisphere summer at 50%, rising to around 75% during autumn and winter 2016-17. Source: Climate Prediction Center.

How unusual is it to slide straight into a La Niña event after an El Niño?

Not at all unusual, says Dr Michael McPhaden, a senior expert in the ocean’s role in climate at the NOAA/Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, US. He tells Carbon Brief:

You can find more information about La Niña on NOAA’s blog, written and maintained by its scientists. In the latest May 2016 update, entitled “Switcheroo!”, Dr Emily Beckersays:

So, what impact will an impending La Niña have on global temperature in 2016?

A record hot start to 2016

So far in 2016, global temperatures have been exceptionally high.

With February, March and April all breaking monthly temperature records by the biggest margins ever recorded, 2016 is looking like a sensible bet for the warmest year on record.

Earlier this month, Dr Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Science, put the chance of 2016 topping the temperature rankings at more than 99%.

Will the coming La Niña alter that picture?

‘A done deal’

Such is the warming seen so far this year that 2016 is likely to retain the top spot, whether or not a La Niña develops, says Cobb. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s likely a done deal, for two reasons.”

One, is that La Niña tends to have a smaller influence on global temperature than her warmer brother. A large event still wouldn’t be enough to redress the balance, Cobb says:

“Even a strong La Niña event later this year will likely not compensate for the warm months we’ve had early in 2016 associated with an exceptionally strong El Niño event.”

Two, is that La Niña typically doesn’t reach a peak until winter, or early the following year. This means the biggest impact on global temperature is likely to come in 2017, not in 2016.

That means that, while La Niña will reduce some of the warmth in the latter part of 2016, it is likely that 2016 will stay in top spot. Scaife predicts:

“There continues to be a high chance that 2016 will be a nominal third record year in a row.”

Other scientists appear a little less keen to call it just yet. McPhaden tells Carbon Brief:

“Global temperatures lag those in the tropical Pacific by several months…How global temperatures will respond in 2016 therefore depends on how quickly La Niña develops and how intense it is.”

Collins suggests it would be unwise to rule out the possibility that 2016 could slip down the rankings. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The last few months have been quite amazing in terms of anomalies, but a large La Niña (if it were to happen) could drag down global temperatures…I expect 2016 will be in the top 10 warmest years on record, but it might not be top if La Niña comes.”

How likely is it that the coming La Niña will turn out to be a big one?

Waiting game

Looking back over past events can help shed some light on this question. The best analogy is the last big El Niño event in 1997/98, says Cobb, which was followed by a strong La Niña.

But while the 1997/8 El Niño was on a par in terms of magnitude, the event now on its way out had some slightly different characteristics. So that analogy can only take us so far, says Cobb:

“It’s a bit of a waiting game right now, in terms of the strength of the La Niña event this coming winter…My bet is for a moderate-to-strong La Niña event.”

Scaife says it’s still a little early to be confident of the strength of La Niña. But, he adds:

“It is extremely unlikely to be as strong as the recent El Niño, which was 2-3C in strength depending on the exact measure used.”

Forecasts of sea surface temperature in the tropical Pacific Niño 3.4 region in 2016. Source: UK Met Office.

Predicting anything about El Niño or La Niña at this time of year is notoriously difficult because so much can still change, warns Collins. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We should be cautious here. We are right at the ‘Spring predictability barrier’ and there are still many months to go before the winter when the anomalies usually peak.”

Prepare for a cooler 2017

If a La Niña does materialise, it’s reasonable to expect global temperature in 2017 to drop compared to what we’re seeing now, says Cobb. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I would expect…cooler global temperatures than we saw in 2015 and 2016, given that a strong La Niña would linger through early 2017, at the very least.”

Scaife agrees with this prediction, telling Carbon Brief:

“Should La Niña grow into a full blown event, then it is likely that 2017 global average temperature will be less warm than 2016, but still much warmer than normal due to climate change.”

On that point of the background warming, it’s worth noting that as the baseline is pushed ever higher, the distinction between typically hot El Niño years and typically cool La Niña years is blurring. The Met Office’s Dr Mark McCarthy tells Carbon Brief:

“Thanks to climate change, a modern La Niña will still be warmer than most past El Niño years.”

McCarthy points to the La Niña in 1999, which followed the large El Niño of 1997-98. That La Niña was still warmer than most preceding years, with the exception of 97/98. He ponders:

“How long until we have a La Niña year that is warmer than the major El Niño of 1998?”

‘Double jeopardy’

If and when a La Niña does appear later this year, its passage is likely to be accompanied by some very extreme weather. Scaife tells Carbon Brief:

“[D]epending on season, La Niña increases the chance of a strong Indian monsoon, an active Atlantic hurricane season, flooding and heavy rainfall in the west Pacific, and further heavy rains in southern Africa and equatorial South America.”

Many of the impacts will simply be the opposite of El Niño, says McPhaden. India, Indonesia and other regions that experienced severe drought during the recent El Niño may see flooding during the La Niña. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That puts some parts of the world in double jeopardy with potential swings from one extreme to another over the course of a year.”

The good news, relatively-speaking, is that scientists’ ability to predict El Niño and La Niña means we can at least prepare for some of the most damaging impacts, says McCarthy.

Seasonal impacts of La Niña. Source: NOAA.

La Niña could bring welcome respite in some parts of the world, Cobb says:

“Australia and those areas in and around the western Pacific should see a relief from the drought conditions they experienced during the 2015/16 El Niño event.”

Potentially, La Niña could even reverse the recent fortunes of the world’s coral reefs,stricken by rising temperatures and widespread bleaching. Cobb tells Carbon Brief:

“As someone who has witnessed devastating coral reef mortality caused by the El Niño event, I am hopeful that a period of cooler-than-average ocean temperatures may give the world’s reefs a much-needed break from acute and prolonged thermal stress.”

For some reef systems, it may be too little too late, Cobb says. But for others, it could mean the difference between life and death.

Carbon Brief will be updating you with the latest on La Niña in the coming months. You can also track its official status on the NOAA pages, or via the Met Office forecasts.

Arguments

Arguments

I think it is important to note that our "cool" La Nina years of the 21st century are still hotter than most of the hot El Nino years of the previous century., with the one exception being the monster El Nino of 1998. Just compare 2008 to all of the years of the 1900's.

That is the state of the climate in this century; a "cool" year in these times would have, not very long ago, been considered an extremely, outrageously hot year. Then our hot years are extermely, outrageously hot even beyond that.

From basic rebuttal #49. UAH temperature chart showing the jump up in both El Niños (Pink lines) and La Niñas (Green lines) post 1997. Unfortunately our dear Skeptic Spencer has revised his chart which eliminates the actual trend seen in this previous version.

Something else rather curious is happening. If you look at the Mana Loa Carbon dioxide readings from April, the increase from the previous April is 4.16ppm. If you look at the series starting from December they are 2.91, 2.56, 3.76, 3.31, 4.16 and May to May, 3.76. Is this some effect of El Nino (less biological activity off the West Coast of South America), the shut down of a carbon sink or two or something else entirely.

william @3, the amount of CO2 that can be drawn down into surface waters of the ocean reduces with increased temperatures, all else being equal. That means that on a subdecadal scale, change in CO2 content from year to year is as much a function of changes in Global Mean Surface Temperature as of net emissions. The decadal trend is still a function of emissions. Consequently, the record hot April just experienced will have resulted in a near record increase in atmospheric CO2, even with no increase in, or even slightly declining CO2 emissions. However, this will be countered by much reduced atmospheric increase with essentially the same emissions next april, which is likely to be effected by a La Nina.

There is no indication that, and it is certainly too little data to conclude that, there has been a shut down of any carbon sink beyond the temperature dependence of absorption of excess emissons that has been observed since 1850.