Amazon drought: A death spiral? (part 2:climate models)

Posted on 1 June 2011 by Rob Painting

This post continues from Part 1

Amazon 'die-back'

A study published 11 years ago, Cox (2000), attracted a lot of attention when, using a coupled climate/carbon-cycle model, the authors projected the Amazon rainforest would undergo dramatic die-back if business-as-usual CO2 emissions continued to the end of the 21st century. This 'die-back' in the simulations was from persistent warming and drying of the Amazon.

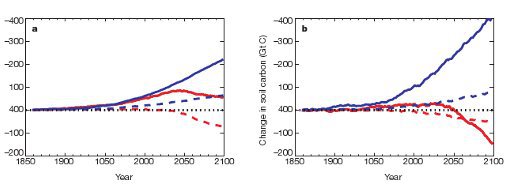

Starting their model runs from 1860 through to the year 2100, Cox (2000) found that the land carbon sink in the Amazon began to decline from around 2010 onwards (meaning vegetation was absorbing less CO2 from the atmosphere) and by about 2040 the Amazon begins to 'die-back'. In the experiment, reduced water recycling in plants (lower stomatal conductance) and loss of carbon stores through higher soil respiration are two mechanisms which speed up the loss of the rainforest.

Figure 1: Effect of global warming on changes in land carbon storage. The red lines represent the fully coupled climate/carbon-cycle simulation, and the blue lines are from the 'offline' simulation which neglects direct CO2-induced climate change. The figure shows simulated changes in vegetation carbon (a) and soil carbon (b) for the global land area (continuous lines) and South America alone (dashed lines). Note typo in a) & b) - year 1050 should be 1950

More dire projections

The spectre of Amazonian 'die-back' has led to a number of other modeling experiments investigating the possibilty of such a scenario. We'll cover a selection of them here, firstly with two other experiments using the same Hadley Centre climate model as Cox (2000).

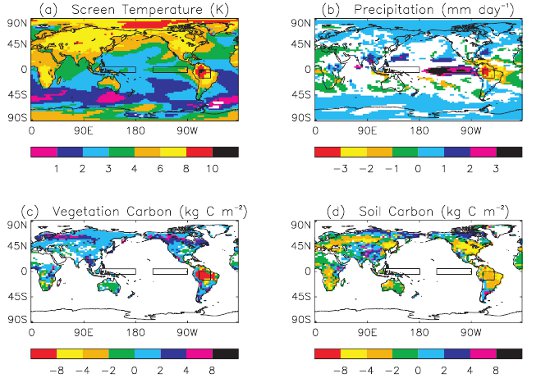

1. Cox (2004) found that the modelled drying in the Amazon is caused by an El Nino-like warming of the tropical Pacific sea surface. The simulations show a greater warming in the east and central Pacific, than in the western Pacific (see figure 2a). Weakening of the Walker Circulation increases rainfall over the Pacific at the expense of rainfall over the Amazon (figure 2b).

Figure 2: Maps of changes in climate and land carbon storage over the 21st century from the fully coupled climate-carbon cycle projections. (a) Screen temperature, (b) precipitation, (c) vegetation carbon and (d) soil carbon. These maps were calculated as the differences between the means for the 2090s and the 1990s. Only areas for which the projected change is greater than 95% signi?cant (according to a paired student t-test) are shown. In each map the box over South America represents the de?nition of Amazonia for the purposes of this study (70°W–50°W, 15°S–0°N), while the boxes over the Paci?c show the NINO3 region (150°W–90°W, 5°S–5°N), and the western Equatorial Paci?c region (120°E–180°E, 5°S–5°N)

Again, an aggravating factor in the experiment is the plant response. Increased atmospheric CO2 leads to reduced water recycling in trees, and this decrease in evapotranspiration causes surface temperatures to rise considerably. So dramatic is this effect, that by 2100 a portion of the Amazon warms by 10°C.

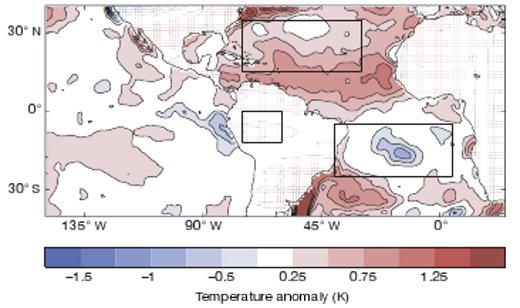

2. Cox (2008) examine the conditions leading up to the extreme 2005 Amazon drought, and find a connection between drying of western Amazonia (small black box in figure 3), and changes in the Atlantic sea surface temperature gradient (two large black boxes in figure 3).

Figure 3: Anomalies in SSTs for July–October 2005, relative to the July–October mean values over the standard climatological period 1961–1990. The black boxes show the regions used in the study

Their modeling experiment reveals that greater warming in the tropical north Atlantic, relative to the south, shifts the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) further north, and results in rainfall reductions over the dry season in western Amazonia.

Another notable finding of Cox (2008) is that reflective aerosol pollution in the northern hemisphere during the 20th century actually served to minimize drying in the western Amazon. By reflecting more sunlight back out to space, aerosols slowed the rate of warming in the tropical Atlantic ocean. The bad news from this finding is that as reflective aerosol pollution falls in the northern hemisphere (due to air quality controls), this will provide an extra boost to warming of the tropical Atlantic, and a further speed up of drying in the western Amazon.

Finally, the authors estimate the probability of the 2005 drought occurring as a 1-in-2 year event by 2025, rising to a 9-in-10 year event by 2060!

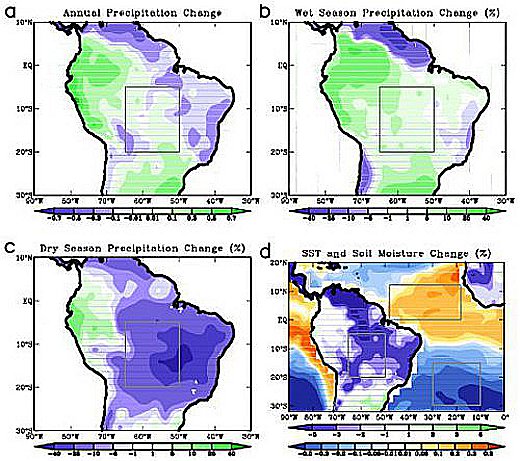

3. Cook (2010) utilize 15 climate models used in the Intergovermental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) AR4. Based on the median of the model runs, they find a greater annual north/south migration of the ITCZ, which tends to slightly increase wet season rainfall and slightly decrease dry season rainfall, but produce a longer dry season. Again the El-nino-like warming of the eastern and central tropical Pacific evolves.

Figure 4: Future changes in the Amazon and surrounding regions according to the median of 15 IPCC models calculated by taking the difference between the mean of the period of 2070–2099 and that of 1961–1990 for: (a) Annual mean precipitation (mmd−1); (b) Wet season precipitation (%); (c) Dry season precipitation (%); (d) Annual sea surface temperature (?C) with its tropical mean removed and annual mean soil moisture (%).

Unlike Cox, they conclude that the western Amazon is unlikely to undergo die-back. The central, and in particular southern amazon, aren't so fortunate; major die-back is expected there.

4. Vergara (2010), using 24 climate models, indicate that the north-western part of the Amazon will see greater rainfall this century, while the southern Amazon dries out. The El Nino-like pattern in the tropical Pacific is observed again, however the tropical Atlantic warming is not simulated in all models. Forest die-back is anticipated in southern and north-eastern Amazonia, with the 21st century likely to produce greater droughts and more intense flooding there.

Common strands

Although reaching slightly different conclusions, the modelling experiments exhibit some common features, namely that:

- changes in Earth's atmospheric circulation, under rising CO2, is the primary cause of the modeled Amazonian die-back. This arises from two features: the future warming of the tropical Pacific and Atlantic sea surface, and general warming of the global sea surface.

- these changes reduce rainfall over the Amazon in the dry season, and also lengthen the dry season.

- further drying comes from reduced water recycling in trees, as they respond to the elevated levels of CO2.

All-in-all some eyebrow-raising results, most of which don't even account for the effects of deforestation, but they also need to be balanced with the knowledge that not all climate models project a drop in Amazon rainfall. Furthermore, the boundary conditions of the experiments differ in certain respects, and some key aspects of modern-day Amazonia are not well represented in the models. Finally and importantly, while it hardly needs reminding, we are after all talking about approximations of the real world.

Despite these caveats, it raises the obvious question: how realistic are the gloomy projections? It's here that recent observations, and paleoclimatology, may provide some insight.

Next: 2005 & 2010 extreme Amazon droughts

Arguments

Arguments

[dana1981] IIRC, studies have shown that more snow tends to fall in winters of hotter years, actually. But this is decidedly off-topic.