A comprehensive review of research into misinformation

Posted on 13 October 2012 by John Cook

Congratulations to John Cook for being co-author on two peer-reviewed papers published this week, Nuccitelli et al. (2012) and the paper discussed in this post, Lewandowsky et al. (2012).

Last November, we released the Debunking Handbook, an introduction to the psychological research into misinformation and practical tips on how to successfully debunk myths. The booklet was intentionally short - briefly covering the research with the emphasis on practical tips for communicators. A more comprehensive scholarly review, Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing, has now been published in the journal Psychlogical Science in the Public Interest (and I'm happy to report the full paper is freely available to the public). The review is a thorough examination of the psychological research into misinformation but also provides a set of practical guidelines that are even more concise than the Debunking Handbook.

Four of the co-authors of the paper are scientists who have conducted much of the research - Stephan Lewandowsky (who gives a detailed two part interview about the paper), Ullrich Ecker (who wrote about the paper in The Conversation & Huffington Post), Colleen Seifert and Norbert Schwarz. The fifth co-author is myself. The paper looks at where misinformation comes from - from rumours, governments, vested interests and yes, the Internet. We explore the psychological research into what makes corrections fail, or even backfire.

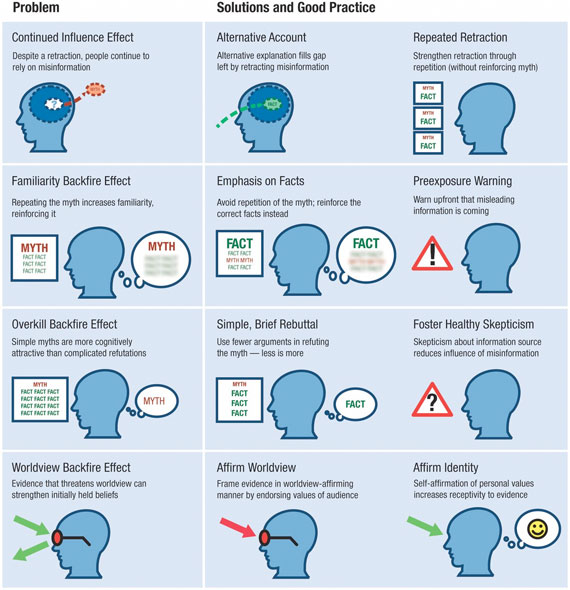

Finally, we provide specific recommendations for the debunking of misinformation. This includes a graphic summary of the various problems to watch out for when you're refuting misinformation and suggested solutions. This is a very handy visual guide which if I'd thought of at the time would've included in the Debunking Handbook. If you find yourself frequently having to respond to misinformation, I suggest downloading this PDF and keeping a print-out near your monitor :-)

The Debunking Handbook and Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing were inspired by the absence of a practical summary of research into how to effectively refute misinformation. There is a wealth of research into this topic and communicators would do well to avail themselves of the existing body of knowledge. Hopefully both documents will prove useful resources in a period when misinformation abounds.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 It should be immediately obvious that there is a fairly simple relationship between the two, falsifying the complexity argument.

But they could be more similar. We need to add in one further factor: The fact that, like an oven, the earth takes a little while to respond to it's control knob. See the red lines in the following figure:

It should be immediately obvious that there is a fairly simple relationship between the two, falsifying the complexity argument.

But they could be more similar. We need to add in one further factor: The fact that, like an oven, the earth takes a little while to respond to it's control knob. See the red lines in the following figure:

This very simple model (20 lines of code) is able to explain 20th century climate pretty well, and project ~50 years into the future. (In fact we now know some of the remaining discrepancies are due to biases in the temperature measurements, not problems with the model!). And it gives the same kind of answers as climate models, estimates from the glacial cycle, and estimates from deep geological time. For a full version of this calculation including uncertainties, see Padilla, Vallis & Rowley 2011.

(Why didn't Hansen do this calculation? Because he didn't have the detailed forcing measurements, and most importantly, the results of the critical last 25 years of our experiment on the atmosphere. He has done it since.)

That's just one line of evidence of many, based on one observable of many. We could look at many more. If you want just one, then look at the Earth's IR spectrum - a pure prediction from theory which was later tested by satellite. Also how it has changed over time.

To put together a probability of climate science being wrong, we'd need to assimilate the probabilities of all the observations fitting a wrong theory, and have an alternative theory which could explain all those observations. And now we run into a piece of social evidence which relates to the initial argument. If we start looking at the alternative hypotheses, we start to see a pattern. The consensus theory is a single consistent theory which explains almost all the available data of many different types from the last 600m years. The alternative hypotheses advanced by different skeptics are inconsistent, and without exception address only a single period and type of data. In other words, they do not appear to be knowledge-building in the way real science does. They have the fingerprint of anti-science.

That's only a start. We can look at the social, political and funding structures. If you haven't read 'Merchants of Doubt', that would be a good place to start. Is it likely that the same actors, financial motivations, and communications strategies which were part of a misinformation campaign when it came to smoking or DDT have suddenly got it right (despite the financial interests) when it comes to climate science.

I don't think anyone has attempted a holistic estimate of the probability of climate science being wrong - the most I have seen is Knutti and Hegerl on the range of likely climate sensitivities - a single variable, ignoring all the additional observations of individual components of the system. Quantifying the social aspects would be harder, but they are going to further reduce rather than increase the chances.

This very simple model (20 lines of code) is able to explain 20th century climate pretty well, and project ~50 years into the future. (In fact we now know some of the remaining discrepancies are due to biases in the temperature measurements, not problems with the model!). And it gives the same kind of answers as climate models, estimates from the glacial cycle, and estimates from deep geological time. For a full version of this calculation including uncertainties, see Padilla, Vallis & Rowley 2011.

(Why didn't Hansen do this calculation? Because he didn't have the detailed forcing measurements, and most importantly, the results of the critical last 25 years of our experiment on the atmosphere. He has done it since.)

That's just one line of evidence of many, based on one observable of many. We could look at many more. If you want just one, then look at the Earth's IR spectrum - a pure prediction from theory which was later tested by satellite. Also how it has changed over time.

To put together a probability of climate science being wrong, we'd need to assimilate the probabilities of all the observations fitting a wrong theory, and have an alternative theory which could explain all those observations. And now we run into a piece of social evidence which relates to the initial argument. If we start looking at the alternative hypotheses, we start to see a pattern. The consensus theory is a single consistent theory which explains almost all the available data of many different types from the last 600m years. The alternative hypotheses advanced by different skeptics are inconsistent, and without exception address only a single period and type of data. In other words, they do not appear to be knowledge-building in the way real science does. They have the fingerprint of anti-science.

That's only a start. We can look at the social, political and funding structures. If you haven't read 'Merchants of Doubt', that would be a good place to start. Is it likely that the same actors, financial motivations, and communications strategies which were part of a misinformation campaign when it came to smoking or DDT have suddenly got it right (despite the financial interests) when it comes to climate science.

I don't think anyone has attempted a holistic estimate of the probability of climate science being wrong - the most I have seen is Knutti and Hegerl on the range of likely climate sensitivities - a single variable, ignoring all the additional observations of individual components of the system. Quantifying the social aspects would be harder, but they are going to further reduce rather than increase the chances.

Comments