Monckton Myth #11: Carbon Pricing Costs vs. Benefits

Posted on 14 February 2011 by dana1981

As part of an ongoing series looking at Christopher Monckton’s response to Mike Steketee and as a new addition to the Monckton Myths, this post examines Monckton’s claims about the costs vs. benefits of carbon pricing. Monckton made the following claim in his comment #24 to Steketee:

As part of an ongoing series looking at Christopher Monckton’s response to Mike Steketee and as a new addition to the Monckton Myths, this post examines Monckton’s claims about the costs vs. benefits of carbon pricing. Monckton made the following claim in his comment #24 to Steketee:

Every serious economic analysis...has demonstrated that the costs of waiting and adapting to any adverse consequences that may arise from “global warming”...would be orders of magnitude cheaper and more cost-effective than any Canute-like attempt to prevent any further “global warming” by taxing and regulating CO2 emissions. It follows that adaptation to the consequences of “global warming” will get easier and cheaper the longer we wait: for then we will only have to adapt to the probably few and minor consequences that will eventually occur, and not until they occur, and only where and to the extent that they occur.

The final portion of this argument is entirely nonsensical. As the planet continues to warm, the adverse consequences of climate change will continue to increase, and thus the costs of adapting to them will continue to rise. Here Monckton is implicitly assuming that the cost of preventing consequences will be less than or equal to the cost of adapting to consequences. If this assumption were correct, it would indeed be most cost-effective to wait and simply adapt to the consequences of climate change. However, as this article will show, Monckton's assumption is incorrect - preventing climate change is significantly cheaper than adapting to it.

Accounting for Benefits

An unfortunate aspect of economic analyses of the impacts of carbon pricing is that they usually only consider the costs of such legislation, while ignoring the benefits associated with slowing global warming. The benefits are essentially the damage avoided by preventing a certain amount of climate change from happening (by reducing carbon emissions). Quite obviously, evaluating the benefits of an action is a key component to any cost-benefit analysis. By ignoring the benefits, it becomes easier to make an argument like Monckton's that the costs of carbon pricing are excessive.

For example, according to a 2010 United States Office of Budget and Management (OMB) Report, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued 30 major environmental regulations from 1999 to 2009 at an estimated cost of $25.8 billion to $29.2 billion. Sounds like a lot of money, right?

Maybe not so much when we also examine the estimated benefits of these regulations, which ranged from $81.9 billion to $533 billion. Clearly ignoring the benefits can lead to a very skewed evaluation of environmental regulations. In the case of these other EPA regulations, $29 billion may sound like a high cost, but the benefits outweighed the costs 3 to 20 times over! The same is true of climate legislation. Perhaps putting a price on carbon emissions will cost $600 billion, but how do these costs compare to the benefits from reducing carbon emissions?

US Climate Action Analysis

The New York University School of Law's Institute for Policy Integrity (IPI) performed a cost-benefit analysis of H.R. 2454: the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (a.k.a. Waxman-Markey - the climate legislation passed by the US House of Representatives). The legislation benefits were estimated by multiplying the estimated amount of greenhouse gas emissions avoided by the monetary valuation of incremental damage from each ton of greenhouse gas emissions (the "social cost of carbon").

Social Cost of Carbon

The social cost of carbon (SCC) is effectively an estimate of the direct effects of carbon emissions on the economy, and takes into consideration such factors as net agricultural productivity loss, human health effects, property damages from sea level rise, and changes in ecosystem services. It is a difficult number to estimate, but is key to any cost-benefit analysis of climate legislation.

The US Department of Energy has used an SCC starting value of $19 per ton, which increases to $68 in 2050 using a discount rate of 3 to 5%. A thorough 2009 inter-agency review of existing estimates SCC puts the starting value at $33 per ton with a 3% discount rate, increasing to $118 in 2050. The EPA estimates the starting value at $68 per ton with a 2% discount rate, increasing to $242 in 2050.

Discount Rate

The term 'discount rate' used above refers to the time value of money - how much more a dollar is worth to us today than next year. A high discount rate means we would much rather have money today than in the future.

In part of Monckton's argument #24 which was omitted from the quote above, he excludes the Stern Review (discussed below) from his category of "serious economic analyses" primarily due to "its absurd near-zero discount rate." The Stern Review used a discount rate of approximately 1.4%. Australian Economist John Quiggin has discussed the Stern Review discount rate and its critics, and notes that a much higher rate is tantamount to telling future generations that they "can go to hell for all we care," since high discount rates place much lower weight on the welfare of future generations.

The choice of discount rate is rather subjective, and a case can certainly be made that the 1.4% value used in the Stern Review is reasonable. However, those who believe a 1.4% discount rate is too low can put more stock in the IPI study, which considered discount rates ranging from 2% to 5%. 3% seems to be the most widely-used value.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

The legislation costs were estimated from analyses performed by the EPA and Congressional Budget Office, as discussed in the "CO2 limits will harm the economy" rebuttal. The direct benefits were estimated using various SCC values. Indirect benefits such as slowing of ocean acidification and incidental reduction in co-pollutants were omitted from the analysis; therefore, the benefit estimates are quite conservative.

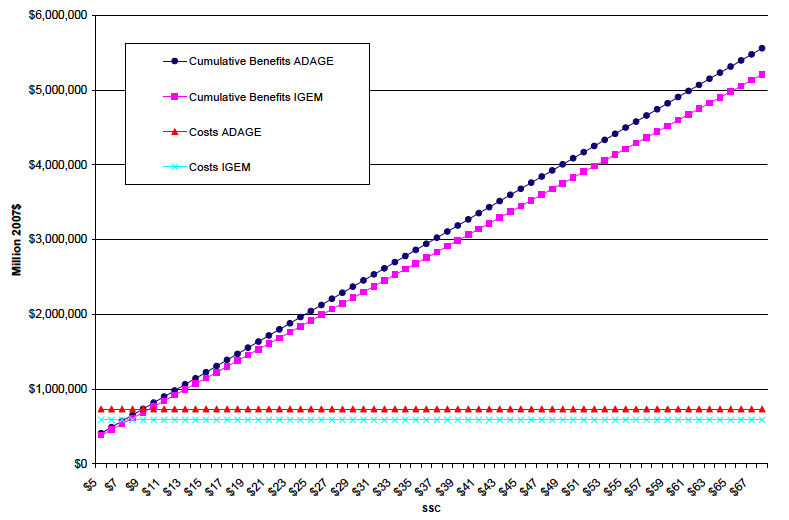

The IPI illustrates how the costs and benefits of H.R. 2454 compare for two economic models (ADAGE and IGEM) in relation to SCC in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Costs (light blue and red points) and Benefits (dark blue and purple points) vs. SSC values ($ per ton of carbon dioxide) for H.R. 2454 using two economic models (ADAGE and IGEM)

As you can see in Figure 1, for an SCC of just $9 per ton of carbon dioxide, the direct benefits of H.R. 2454 match the costs, and for any higher value of SCC, the benefits outweigh the costs. Using the DOE SCC of $19, the direct benefits exceed the costs by a factor of 2.3. Using the inter-agency SCC of $33, the ratio rises to 4. Using the EPA SCC of $68, direct benefits outweigh costs by a factor of 8.3. The IPI cost-benefit analysis concluded as follows.

Using conservative assumptions, the benefits of H.R. 2454 could likely exceed the costs by as much as nine?to?one, or more.

The estimated benefits do not include a significant number of ancillary and un?quantified benefits, such as the reduction of co?pollutants (particularly sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide), the prevention of species extinction, and lower maintenance costs for energy infrastructure. Due to those limitations, the benefits estimates should be considered to be very conservative."

Global Climate Action Cost-Benefit Analysis

The benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions can also be viewed as the cost of doing nothing. The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change is perhaps the most well-known evaluation of this cost. The Stern Review estimated that taking no action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would cost 5% to 20% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2100. The Stern Report also estimated that reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change can be limited to around 1% of global GDP each year. Assessments of proposed climate legislation in the USA have also concluded that they would signigficantly reduce the country's greenhouse gas emissions at a cost on the order of 1% of national GDP.

Another report by the German Institute of Economic Research concluded that "If climate policy measures are not introduced, global climate change damages amounting to up to 20 trillion US dollars can be expected in the year 2100....The costs of an active climate protection policy implemented today would reach globally around 430 billion US dollars in 2050 and around 3 trillion US dollars in 2100."

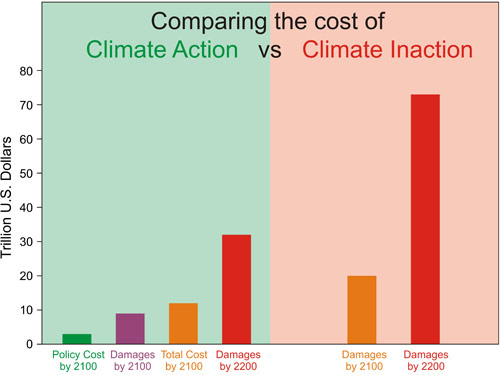

A study prepared for the European Commission's Directorate General-Environment evaluated the costs and benefits of various atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration scenarios (Watkiss et al. 2005). The study found that in their 450 parts per million (ppm) atmospheric CO2 concentration scenario (590 ppm by 2200), the total damage caused by climate change would amount to $32 trillion by the year 2200. In the IPCC A2 scenario (815 ppm by 2100, 1,450 ppm by 2200), the climate change-caused damage by 2200 is $73 trillion. In other words, if we achieve the internationally-accepted goal of limiting atmospheric CO2 to approximately 450 ppm this century, the global economic benefit will be approximately $41 trillion by 2200.

In all of these analyses, the benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions outweigh the costs by trillions of dollars. Combining the results of the German Institute for Economic Research and Watkiss et al. studies, we find that the total cost of climate action (cost plus damages) in 2100 is approximately $12 trillion, while the cost of inaction (just damages) is approximately $20 trillion (Figure 2). This figure is also available in the Skeptical Science Hi Rez Climate Graphics.

Figure 2: Approximate costs of climate action (green) and inaction (red) in 2100 and 2200. Sources: German Institute for Economic Research and Watkiss et al. 2005

Economists Support Climate Action

Most economists who study the economics of climate change agree that action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is necessary. As Robert Mendelsohn (professor of forest policy and economics at Yale University) put it, "The [economic] debate is how much and when to start." Some economists believe that we should immediately put a high price on carbom emissions, while others like Yale's William Nordhaus believe we should start with a low carbon price and gradually ramp it up.

In a recent interview, Nordhaus - whose models project a smaller economic impact than most - said that regardless of whether the models showing larger or smaller economic impacts from climate change are correct, "We’ve got to get together as a community of nations and impose restraints on greenhouse gas emissions and raise carbon prices. If not, we will be in one of those gloomy scenarios."

How Much Are You Worth?

One flaw in these economic studies is that it's very difficult to put a price on things like biodiversity, cultural diversity, human life, etc. For example, if unabated climate change results in a famine in Kenya, or the Maldives is lost to rising sea levels, the loss of life and culture won't have much impact on the global economy, but I think we can all agree that there is a significant non-economic loss associated with these types of events. Likewise if a number of species fail to adapt to the rapidly changing climate, the loss associated with this reduction in biodiversity goes beyond whatever small economic impact is modeled in these studies.

Summary

Cost-benefit analyses of proposals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have consistently concluded that the benefits far outweigh the costs. In the USA, the direct benefits of the legislation which was passed by the House of Representatives (but later killed by the Senate) would have outweighed the costs by a factor of 2 to 9 (a net savings of at least $1 trillion by 2050), under conservative assumptions (ignoring indirect benefits such as reduction of co-pollutants and ocean acidification).

Analyses of global carbon emissions reductions scenarios all show that the benefits outweigh the costs by trillions of dollars. Most economists agree that steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are necessary - the debate is not whether we need to put a price on carbon emissions, but how high the price should be.

Monckton's Point #24 is Wrong

In the studies discussed above, the benefits are effectively equivalent to the costs of adaption if we fail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In all of these analyses, the benefits significantly outweighed the costs of putting a price on carbon emissions. Therefore, we have here four examples of eceonomic analyses concluding that the costs of pricing carbon are much lower than the costs of adapting to climate change.

Let us once again examine Monckton's assertion #24.

Every serious economic analysis...has demonstrated that the costs of waiting and adapting to any adverse consequences that may arise from “global warming”...would be orders of magnitude cheaper and more cost-effective than any Canute-like attempt to prevent any further “global warming” by taxing and regulating CO2 emissions.

The four economic analyses discussed above are certainly "serious." It would be difficult to argue otherwise; however, since Monckton has not provided a single example of an economic analysis which concludes that the costs of adaptation will be less than the costs of carbon pricing, it is difficult to ascertain exactly what he considers a "serious economic analysis."

The conclusions of these studies also raise a key question - if economic analyses consistently show that not only will the costs of putting a price on carbon emissions be minimal, but the benefits will significantly outweigh the cost, what exactly are we waiting for?

This post was written by Dana Nuccitelli (dana1981) has been incorporated into the Intermediate version of the skeptic argument "CO2 limits will harm the economy".

Arguments

Arguments

DViscount Monckton to come and see for himself; but really I would prefer him to stay away. One unexpected consequence of a revenue-neutral carbon tax is that is hard to repeal, since abandoning it would entail raising income taxes. Hardly a populist move. Martin Weitzman of Harvard University argues that most cost-benefit analyses don't properly factor in the low possibility of the disastrous outcomes that lurk in the fat tails of climate forecasts. It's worth noting that most probability distributions related to climate are skewed to the high (bad) side and while truly bad outcomes (let's say higher than 6 degrees Celsius by the end of the century) are improbable, they are often given chances of happening of about 3%. With appreciable possibilities like this of truly dire outcomes, it may make little sense to sweat the economics about whether action is needed or not. Perhaps if we had 30 planets it might be interesting to run experiments to see which course of action yielded the highest return on investment. But we don't, of course, even though people like Monckton do seem to inhabit an alternative reality.