Acidification: Oceans past, present & yet to come

Posted on 31 March 2011 by Rob Painting

Through the burning of fossil fuels, humans are rapidly altering the chemistry of the global oceans, making seawater increasingly more acidic. Most attention to date has focused on what we might expect in the years to come, and rightly so, many studies have shown that the seas of the future are likely to be corrosive to shell-building marine life. Some areas, such as the Arctic, might even reach a corrosive state within a decade. But, knowing that ocean acidity has increased by almost 30% since the beginning of the industrial civilization, has the change so far already had an effect on marine life?

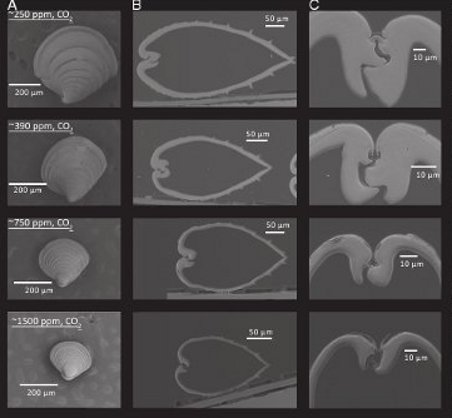

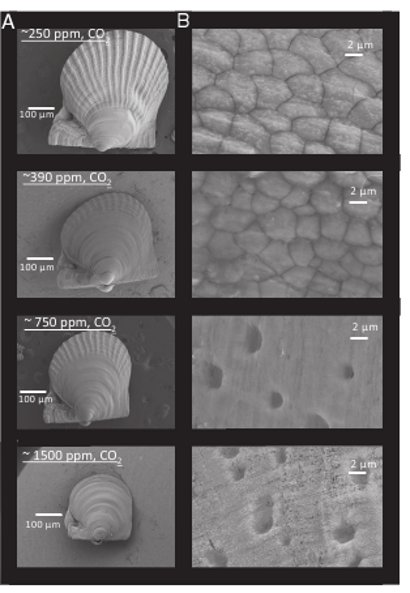

Talmage and Gobler 2010 sought an answer to this question by examining growth and shell formation in two shellfish species, the Northern Quahog hard clam and the Bay scallop. In lab experiments they grew juveniles in seawater at various levels of pH representing the global average for specific points in time, pre-industrial (250ppm atmospheric CO2), modern day (390ppm), and CO2 levels expected by the year 2100 (750ppm) and 2200 (1500ppm) under moderate business as usual scenarios.

Figure 1 - Microscope image of Northern quahog hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) under various levels of CO2 at 36 days old. A= individual juvenile at each CO2 level. B= side cross section of shell at each CO2 level. C= hinge close-up at each level.

Figure 2- Microscope images of 52 day old Bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) grown under different levels of CO2. A= Individual juvenile at each CO2 level. B= Close-up of outermost shell for each juvenile at each CO2 level.

Not surprisingly, the 750ppm and 1500ppm states induced shells that are thinner, smaller and weaker, as well as low rates of survival for juveniles. In contrast, under pre-industrial levels (250ppm), the improvement in health and survival was significant. Shells were much larger, thicker and more strongly built than under modern day conditions, and survival rates were double that of modern day (40% vs 20% after 38 days for the hard clam).

Even under ideal conditions, mortality is high among juvenile shellfish populations, and this study reveals that not only does the death rate increase along with seawater acidity, the shells are smaller, thinner, more fragile and internal organs are less healthy. Not exactly desirable traits for a shellfish.

These experiments suggest that ocean acidification has already had a negative impact on shellfish populations over the last two centuries. Alongside pollution and increased nutrient run-off from industrial farming, ocean acidification might be yet another factor in the rapid decline of wild shellfish populations.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 I've yet to find a graphic which adequately describes the process, but bear with me:

Equation 2 Carbonic acid easily breaks down releasing excess hydrogen ions and drives the pH of seawater down (pH being a measure of the concentration of hydrogen ions. More hydrogen ions = lower pH ).

Equation 3 Here's where the buffering part kicks in, some of the excess hydrogen ions combine with carbonate ions to form bicarbonate ions. This last step serves to buffer the acidification because it reduces the concentration of hydrogen ions. So without this last reaction, the pH would be lower.

He seems to be referring to geological processes which increase alkalinity (often balancing out volcanic CO2 output) which takes place over the timescale of tens of thousands of years.

I've yet to find a graphic which adequately describes the process, but bear with me:

Equation 2 Carbonic acid easily breaks down releasing excess hydrogen ions and drives the pH of seawater down (pH being a measure of the concentration of hydrogen ions. More hydrogen ions = lower pH ).

Equation 3 Here's where the buffering part kicks in, some of the excess hydrogen ions combine with carbonate ions to form bicarbonate ions. This last step serves to buffer the acidification because it reduces the concentration of hydrogen ions. So without this last reaction, the pH would be lower.

He seems to be referring to geological processes which increase alkalinity (often balancing out volcanic CO2 output) which takes place over the timescale of tens of thousands of years.

Comments