Can renewables provide baseload power?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Intermediate

Intermediate

|

Advanced

Advanced

| |||

|

Numerous case studies on both regional and global scales have determined that renewable energy, if properly implemented, can provide baseload power. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Renewables can't provide baseload power

The myth that renewable energy sources can't meet baseload (24-hour per day) demand has become quite widespread and widely-accepted. After all, the wind doesn't blow all the time, and there's no sunlight at night. However, detailed computer simulations, backed up by real-world experience with wind power, demonstrate that a transition to 100% energy production from renewable sources is possible within the next few decades.

Reducing Baseload Demand

Firstly, we currently do not use our energy very efficiently. For example, nighttime energy demand is much lower than during the day, and yet we waste a great deal of energy from coal and nuclear power plants, which are difficult to power up quickly, and are thus left running at high capacity even when demand is low. Baseload demand can be further reduced by increasing the energy efficiency of homes and other buildings.

Renewable Baseload Sources

Secondly, some renewable energy sources are just as reliable for baseload energy as fossil fuels. For example, bio-electricity generated from burning the residues of crops and plantation forests, concentrated solar thermal power with low-cost thermal storage (such as in molten salt), and hot-rock geothermal power. In fact, bio-electricity from residues already contributes to both baseload and peak-load power in parts of Europe and the USA, and is poised for rapid growth. Concentrated solar thermal technology is advancing rapidly, and a 19.9-megawatt solar thermal plant opened in Spain in 2011 (Gemasolar), which stores energy in molten salt for up to 15 hours, and is thus able to provide energy 20 hours per day on average, and 24 hours per day during much of the summer.

Addressing Intermittency from Wind and Solar

Wind power is currently the cheapest source of renewable energy, but presents the challenge of dealing with the intermittency of windspeed. Nevertheless, as of 2011, wind already supplies 24% of Denmark's electricity generation, and over 14% of Spain and Portugal's.

Although the output of a single wind farm will fluctuate greatly, the fluctuations in the total output from a number of wind farms geographically distributed in different wind regimes will be much smaller and partially predictable. Modeling has also shown that it's relatively inexpensive to increase the reliability of the total wind output to a level equivalent to a coal-fired power station by adding a few low-cost peak-load gas turbines that are opearated infrequently, to fill in the gaps when the wind farm production is low (Diesendorf 2010). Additionally, in many regions, peak wind (see Figure 4 below) and solar production match up well with peak electricity demand.

Current power grid systems are already built to handle fluctuations in supply and demand with peak-load plants such as hydroelectric and gas turbines which can be switched on and off quickly, and by reserve baseload plants that are kept hot. Adding wind and solar photovoltaic capacity to the grid may require augmenting the amount of peak-load plants, which can be done relatively cheaply by adding gas turbines, which can be fueled by sustainably-produced biofuels or natural gas. Recent studies by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that wind could supply 20-30% of electricity, given improved transmission links and a little low-cost flexible back-up.

As mentioned above, there have been numerous regional and global case studies demonstrating that renewable sources can meet all energy needs within a few decades. Some of these case studies are summarized below.

Global Case Studies

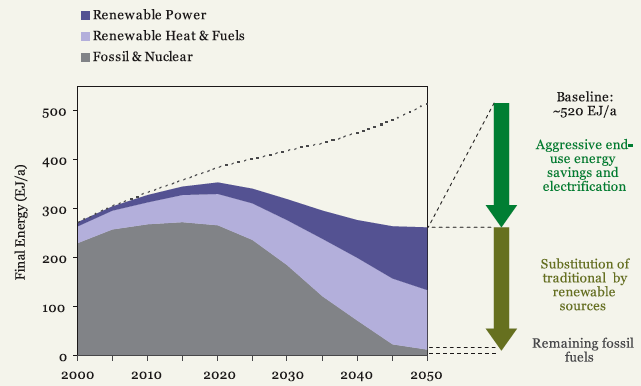

Energy consulting firm Ecofys produced a report detailing how we can meet nearly 100% of global energy needs with renewable sources by 2050. Approximately half of the goal is met through increased energy efficiency to first reduce energy demands, and the other half is achieved by switching to renewable energy sources for electricity production (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ecofys projected global energy consumption between 2000 and 2050

Stanford's Mark Jacobson and UC Davis' Mark Delucchi (J&D) published a study in 2010 in the journal Energy Policy examining the possibility of meeting all global energy needs with wind, water, and solar (WWS) power. They find that it would be plausible to produce all new energy from WWS in 2030, and replace all pre-existing energy with WWS by 2050.

In Part I of their study, J&D examine the technologies, energy resources, infrastructure, and materials necessary to provide all energy from WWS sources. In Part II of the study, J&D examine the variability of WWS energy, and the costs of their proposal. J&D project that when accounting for the costs associated with air pollution and climate change, all the WWS technologies they consider will be cheaper than conventional energy sources (including coal) by 2020 or 2030, and in fact onshore wind is already cheaper.

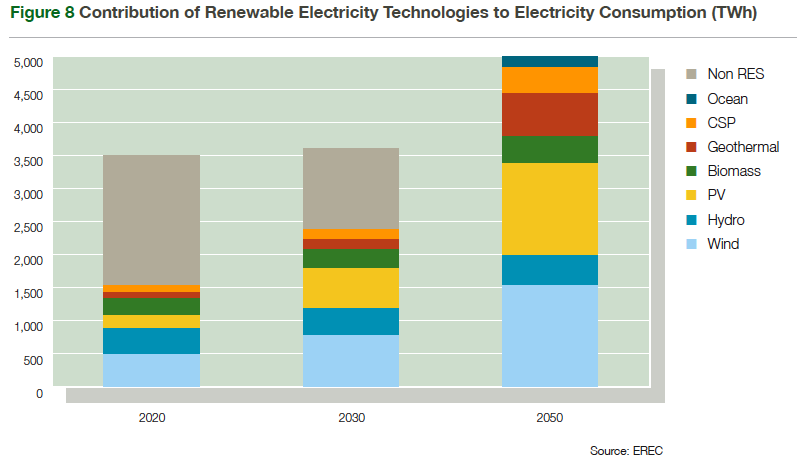

European Union Case Study

The European Renewable Energy Council (EREC) prepared a plan for the European Union (EU) to meet 100% of its energy needs with renewable sources by 2050, entitled Re-Thinking 2050. The EREC plan begins with an average annual growth rate of renewable electricity capacity of 14% between 2007 and 2020. Total EU renewable power production increases from 185 GW in 2007 to 521.5 GW in 2020, 965.2 GW in 2030, and finally 1,956 GW in 2050. In 2050, the proposed EU energy production breakdown is: 31% from wind, 27% from solar PV, 12% from geothermal, 10% from biomass, 9% from hydroelectric, 8% from solar thermal, and 3% from the ocean (Figure 2).

Figure 2: EREC report breakdown of EU energy production in 2020, 2030, and 2050

Northern Europe Case Study

Sørensen (2008) developed a plan through which a group of northern European countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Germany) could meet its energy needs using primarily wind, hydropower, and biofuels. Due to the high latitudes of these countries, solar is only a significant contributor to electricity and heat production in Germany. In order to address the intermittency of wind power, Sørensen proposes either utilizing hydro reservoir or hydrogen for energy storage, or importing and exporting energy between the northern European nations to meet the varying demand. However, Sørensen finds:

"The intermittency of wind energy turns out not to be so large, that any substantial trade of electric power between the Nordic countries is called for. The reasons are first the difference in wind regimes...and second the establishment of a level of wind exploitation considerably greater that that required by dedicated electricity demands. The latter choice implies that a part of the wind power generated does not have time-urgent uses but may be converted (e.g. to hydrogen) at variable rates, leaving a base-production of wind power sufficient to cover the time-urgent demands."

Britain Case Study

The Centre for Alternative Technology prepared a plan entitled Zero Carbon Britain 2030. The report details a comprehensive plan through which Britain could reduce its CO2-equivalent emissions 90% by the year 2030 (in comparison to 2007 levels). The report proposes to achieve the final 10% emissions reduction through carbon sequestration.

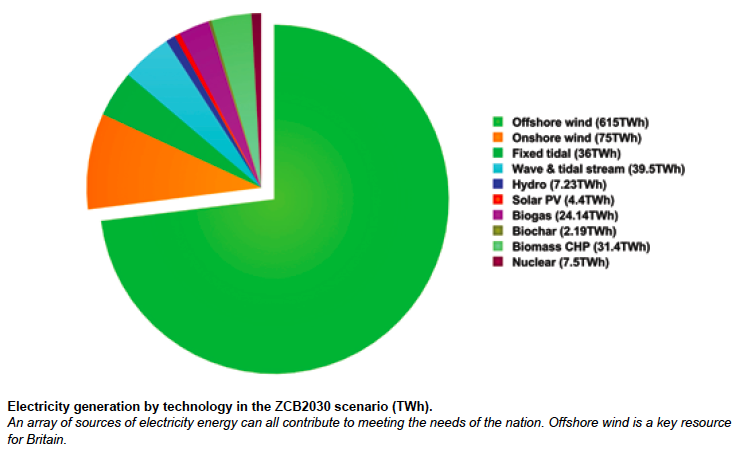

In terms of energy production, the report proposes to provide nearly 100% of UK energy demands by 2030 from renewable sources. In their plan, 82% of the British electricity demand is supplied through wind (73% from offshore turbines, 9% from onshore), 5% from wave and tidal stream, 4.5% from fixed tidal, 4% from biomass, 3% from biogas, 0.9% each from nuclear and hydroelectric, and 0.5% from solar photovoltaic (PV) (Figure 3). In this plan, the UK also generates enough electricity to become a significant energy exporter (174 GW and 150 terawatt-hours exported, for approximately £6.37 billion income per year).

Figure 3: British electricity generation breakdown in 2030

In order to address the intermittency associated with the heavy proposed use of wind power, the report proposes to deploy offshore turbines dispersed in locations all around the country (when there is little windspeed in one location, there is likely to be high windspeed in other locations), and implement backup generation consisting of biogas, biomass, hydro, and imports to manage the remaining variability. Management of electricity demand must also become more efficient, for example through the implementation of smart grids.

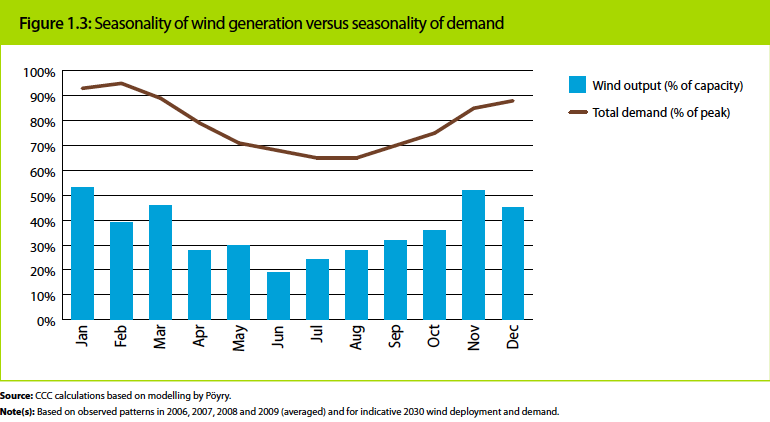

The heavy reliance on wind is also plausible because peak electricity demand matches up well with peak wind availability in the UK (Figure 4, UK Committee on Climate Change 2011).

Figure 4: Monthly wind output vs. electricity demand in the UK

The plan was tested by the “Future Energy Scenario Assessment” (FESA) software. This combines weather and demand data, and tests whether there is enough dispatchable generation to manage the variable base supply of renewable electricity with the variable demand. The Zero Carbon Britain proposal passed this test.

Other Individual Nation Case Studies

Plans to meet 100% of energy needs from renewable sources have also been proposed for various other individual countries such as Denmark (Lund and Mathiessen 2009), Germany (Klaus 2010), Portugal (Krajačić et al 2010), Ireland (Connolly et al 2010), Australia (Zero Carbon Australia 2020), and New Zealand (Mason et al. 2010). In another study focusing on Denmark, Mathiesen et al 2010 found that not only could the country meet 85% of its electricity demands with renewable sources by 2030 and 100% by 2050 (63% from wind, 22% from biomass, 9% from solar PV), but the authors also concluded doing so may be economically beneficial:

"implementing energy savings, renewable energy and more efficient conversion technologies can have positive socio-economic effects, create employment and potentially lead to large earnings on exports. If externalities such as health effects are included, even more benefits can be expected. 100% Renewable energy systems will be technically possible in the future, and may even be economically beneficial compared to the business-as-usual energy system."

Summary

Arguments that renewable energy isn't up to the task because "the Sun doesn't shine at night and the wind doesn't blow all the time" are overly simplistic.

There are a number of renewable energy technologies which can supply baseload power. The intermittency of other sources such as wind and solar photovoltaic can be addressed by interconnecting power plants which are widely geographically distributed, and by coupling them with peak-load plants such as gas turbines fueled by biofuels or natural gas which can quickly be switched on to fill in gaps of low wind or solar production. Numerous regional and global case studies – some incorporating modeling to demonstrate their feasibility – have provided plausible plans to meet 100% of energy demand with renewable sources.

Last updated on 21 June 2011 by dana1981.

Arguments

Arguments

Note the older version of this thread also addresses many of these points.

[dana1981] My moped runs on solar energy. A lot of peoples' cars run on solar energy, too. I'll be one of them in a few years. Fossil fuels are already more costly than renewable energy, and that includes coal. Try reading the Renewable energy is too expensive rebuttal. Right now the "free market" doesn't take into account the full costs of fossil fuel energy. Not even close. Economists hate it - it's a market failure. That's the point of a carbon price, to make the free market work better.

[DB] "stop with insulting metaphor like "Your attempt to poison the water""

Straw man. Tom criticizes your methods, not your motives (as your quotation from the Comments Policy clearly points out). No style points here are awarded for rhetorical techniques employed.

In the future, please better adhere to the Comments Policy yourself rather than attempting to use it to chastise others. And sticking to facts and citable sources from the peer-reviewed literature will better support your position instead of snark and sarcasm.