What happens if we overshoot the two degree target for limiting global warming?

Posted on 18 December 2014 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Roz Pidcock

Two degrees is the internationally-agreed target for limiting global warming, and has a long history in climate policy circles. Ambition that we can still achieve it is running high as climate negotiators gather in Lima to lay the groundwork for a potential global deal in 2015.

But against this optimistic backdrop, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. With each passing year the scale of the task looms ever larger. There are very real questions about whether or not the world will be able to stay below the two degree limit.

So what happens if we fail to meet the two degree target? What would it mean to resign ourselves to a post-two degree world? And if not two degrees, then what?

As temperatures rise, so do the risks

Two degrees above pre-industrial temperature has been agreed by countries as an appropriate threshold beyond which climate change risks become unacceptably high.

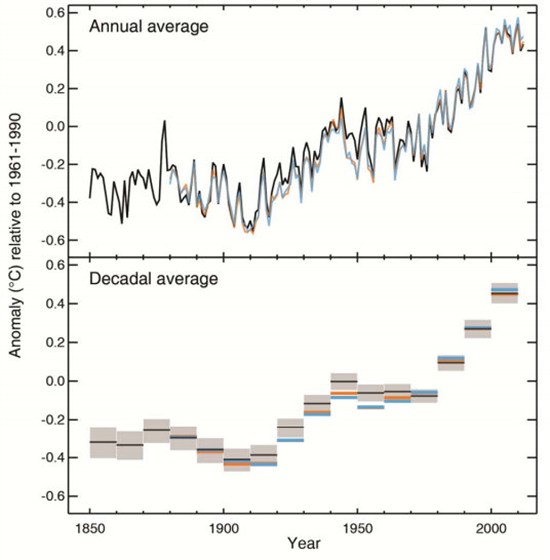

Global temperature has risen 0.85 degrees Celsius since 1880, according to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

We could be due another couple of tenths on top of that as past emissions take a decade or so to reach their full effect warming. Together with current and expected emissions we're essentially already committed to about one degree of warming, scientists estimate.

Observed global mean temperature from 1850 to 2012, relative to the 1961-1990 average. Coloured lines represent three different datasets. Top panel shows yearly averages, bottom shows decadal averages. Source: IPCC 5th Assessment Report

While the international community uses two degrees as the rule-of-thumb threshold for "dangerous" warming, some climate impacts are already locked-in, particularly for low-lying and island nations. Professor Anders Levermann from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Change Research tells us:

"At one degree we are already experiencing damages. Sea level rise in the long term ... is somewhere in the vicinity of two metres. That puts cities like New York, Calcutta and Shanghai in difficult positions, and they need to protect themselves."

Rising temperatures have consequences for food and water security, infrastructure, ecosystems, health and the risk of conflict, says the IPCC. And the higher the temperature, the greater the risk those climate change impacts will be serious and damaging.

One of the most direct impacts society feels from climate change is the greater frequency and intensity of extreme weather.In Europe, heatwaves like the 2003 event which killed 70,000 people are already ten times more likely than a decade ago. In the UK, climate change is making extreme wet winters like last year's about 25 per cent more likely, scientists estimate.

Given that impacts scale with rising temperature, two degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels is thought to represent a climate target that's both achievable and doesn't expose us risks that are too difficult to manage.

But suppose we collectively decide the task of keeping to this target is too great, or the price of swift mitigation too high. What are the consequences of exceeding our self-imposed limit?

Three degrees

The IPCC uses four pathways to illustrate how greenhouse gases could evolve this century. The lowest, RCP2.6, is designed to show how warming could be kept below two degrees above pre-industrial levels (blue line in the graph below).

(Note that temperatures in the graph are relative to the 1986 to 2005 baseline, so add 0.61 degrees to get warming above pre-industrial levels.)

If we aim instead to stay in line with IPCC's second scenario, RCP4.5, that should see global temperature level out at about three degrees above pre-industrial levels (green line).

Extension of the IPCC's emissions scenarios to 2300. RCP2.6 limits warming to two degrees above pre-industrial levels (blue), RCP4.5 levels out as about three degrees (green). In RCP8.5, temperatures exceed four degrees by 2100 and continue to rise. Meehl et al., (2013)

But even accepting this level of risk would require a strong commitment to mitigation. In the IPCC's three degrees scenario, global emissions peak around 2040 and start to decline. But the risks at three degrees are already very high, says Levermann:

"Three degrees of warming increases the risk of strong sea level rise from, for example Antarctica, or the collapse of marine ecosystems, such as Arctic sea ice or coral reefs … [It] increases the risk of intensification of extreme events ... In short, beyond two degrees of warming we are leaving the world as we know it."

Four degrees

In the IPCC's most extreme scenario, RCP8.5, global temperature reaches more than four degrees above pre-industrial levels by 2100. And unless emissions cease altogether, temperatures will continue to rise long past the end of the century.

With emissions accelerating faster than they are now for the next few decades, global temperature rise in RCP8.5 reaches five degrees by about 2120 and six degrees by 2150. This is a worst-case scenario, says Levermann, but that doesn't mean it's not a possibility.

Professor Richard Betts from the UK's Met Office is the coordinator of a new international project called Helix, which looks at the impact of very high levels of warming. He tells us:

"[I]t's very difficult indeed to know what a two degree world will look like, let alone four degrees or even six."

But as the latest IPCC report notes, it's clear the risk of triggering very large, abrupt or irreversible changes in the climate system increases the higher temperatures get:

"With increasing warming, some physical systems or ecosystems may be at risk of abrupt and irreversible changes … Risks increase disproportionately as temperature increases between one to two degrees Celsius of additional warming and become high above three degrees Celsius"

Since temperatures have risen almost one degree already, three degrees "additional warming" here means about four degrees above pre-industrial levels in total.

Continued warming will at some stage trigger the Greenland ice sheet to gradually collapse, although scientists can't say precisely at what temperature this would occur, the IPCC report says:

"For sustained warming greater than some threshold, near-complete loss of the Greenland ice sheet would occur over a millennium or more, contributing up to seven metres of global mean sea level rise."

Natural ecosystems are also set to suffer under higher temperatures, Betts tells us:

"Most life on Earth tends to be adapted to its current conditions, so if conditions change then species either need to move ... or adapt to new conditions, or die out. [The] resilience of the natural world seems to be being reduced as a direct consequence of other human actions, through land use and habitat loss, so it's a double-whammy for ecosystems."

Understanding how rising global temperature translates to risks for society and natural ecosystems is critical to prepare for, and strive to reduce, the scale of impacts. But predicting consequences for different regions is difficult because while global temperature is a good indicator of global change, local impacts can be much more pronounced, Levermann says.

A comparison of climate impacts across the world by the end of the century under RCP2.6 and RCP8.5. (a) Average surface temperature, (b) average annual rainfall, (c) Arctic sea ice extent and (d) change in ocean pH. Source: IPCC 5th Assessment Report

A continuum, not a precipice

For international climate policy purposes, it makes sense to think in terms of the climate damages expected at different degrees of warming.

Two degrees is an appropriate middle ground between what we can no longer avoid and the level of further risk we're willing to accept, Levermann suggests.

"We can't really keep to one degree target anymore … At three degrees warming, Greenland is going to vanish and corals are going to be largely extinct … I would personally argue three degrees is too much and one degree is no longer achievable so two degrees is a reasonable target, but that is for society to decide."

But setting two degrees as a boundary into "dangerous" climate change only works as a political target if its understood as a point along a continuum, not as a climate precipice, Levermann warns.

In other words, failing on the two degree target doesn't mean we should all give up and go home. But admitting defeat means accepting a greater level of risk - and at that point preventing temperatures straying too far above two degrees should be paramount.

As to what counts as unacceptably high risk, that comes down to a judgement call, Betts concludes:

"How much these changes 'matter' or not is largely a matter of personal values and ethics … [W]e have to judge whether we think the benefits to ourselves are worth the risks to other species or future generations of our own."

Only a few years on since countries agreed on two degrees as an appropriate level of climate ambition, it's important to remember the science that underpins the agreement. As Professor Rowan Sutton told a Royal Society meeting this week, decision-making on climate comes down to our appetite for risk. Any decision to expose ourselves to higher climate risk should at least be a conscious and deliberate one, if not necessarily a prudent one.

Arguments

Arguments

A question: The World Bank commissioned report from 2012 about the prospects of a 4C warmer world states: "Even with the current mitigation commitments and pledges fully implemented, there is roughly a 20 percent likelihood of exceeding 4°C by 2100. If they are not met, a warming of 4°C could occur as early as the 2060s." You cite "the most extreme scenario" as being a 4C rise by 2100 at the earliest. This is quite a discrepancy - almost a 'halving' of the time period (from 2012) for such a rise. What is the disrepancy....is it possible that it is due to an inherently conservative nature of the IPCC projections? (that is, assuming the mitigation commitments are NOT met, something that the world has amply demonstrated to be a possible if not probable outcome).

[JH] You are now skating on the thin ice of excessive repetition which is banned by the SkS Comments Policy.

Please note that posting comments here at SkS is a privilege, not a right. This privilege can be rescinded if the posting individual treats adherence to the Comments Policy as optional, rather than the mandatory condition of participating in this online forum.

Please take the time to review the policy and ensure future comments are in full compliance with it. Thanks for your understanding and compliance in this matter.

The above was meant for another commenter. My bad and my apologies!

I look forward to a response to this seemingly very important question. I don't see where the unacceptable repetiton occurs, that the moderator JH has admonished dagold for.

[JH] Ooops! My comment was meant for another commenter, not dagold. My bad!

As Professor Richard Alley states in seversl lectures of his I have watched on Youtube... the uncertianty is on the upside and it is not our friend. We should be mitigating because we might get 4C+, the thought of actually hitting 4C+ is... nearly unimaginable.

Professor Wanless from Miami U>

and yet some places (In Australia, Queensland and New South Wales) aren't doing infrastructure planning for any rise at all by 2100 and some for only 0.8.. We should be planning for 4m. If you plan for 4m and you 2m, no issue, if you plan for 0.8m and you get 2m ... well... You will want to take a whole lot of tax to undo your planning "incompetence."

Unfortunately the discussion of the science and the clearly indicated required changes of how people can enjoy their life appears destined to lead to an insufficient response from leadership in current society.

Levermann's end of comment "... but that is for society to decide." is the crux. How can the future global society that will have to deal with these consequences influence the decisions made by today's society? The problem is the lack of consequences to the leaders of the current global powerful and wealthy societies (leaders of politics, industry, and finance).

The science has been strong and continues to get stronger. Yet people who are undeniably aware of the science continue to attempt to increase profit taking from activities known to need to be curtailed. As a result, the 'target' temperature will increase until there are meaningful consequences for the powerful people in a current society who knowingly deny and resist the need to act more decently.

Continued development of the science will strengthen the case for penalties against those who willfully try to benefit in ways they understand they should not (including carbon taxes). Hopefully some of the worst actors will be penalized retroactively for past actions. When that first such 'significant penalty' is effectively applied to a wealthy and once powerful person the motivation for more decent behaviour will grow and we can then begin meaningfully forecasting the likely maximum global temperature.

The latest C02 levels are now very close to passing the 400 ppm level again which may mean that 2015 could be the first year that remains above that level throughout. This seems to indicate that C02 levels are still increasing at an accelerating rate. Quite how we can even consider achieving a limit on future warming seems more based on optimism than science until we can stabilize C02 levels at their current level.

it is speculated that the sun is entering another "maunder minimum"... in doing some online research about that event, the associated "little ice age" was caused by an estimated -.4 C degree cooling, from decreased solar output.

if -.4 C created that much change, how is that +2 degrees C is considered acceptable?

shastatodd... A new Maunder minimum is highly speculative, but even if it were to occur, it would likely have only a small influence on global temperature trends. Radiative forcing for solar is on the order of 0.05W/m2, whereas the change for anthropogenic forcing is >2W/m2.

Solar barely registers relative to man-made causes.

Further to Rob's comment, I dont know what you are using as your source of information on the LIA, but I would strongly recommend you read the chapter in the IPCC report (paleoclimate) for a summary of the science to date on the LIA. It is more accurate to say that the maunder minimum contributed to the LIA than caused it. To get a better idea of the effect of the Grand minimum alone, then it would be best to look at the Southern hemisphere climate in the LIA.

You can see here to comment on what a Grand minimum would bring. +2 is no picnic but projecting from LIA is too extreme.

shastatodd@6,

The amount of climate difference resulting from only the 0.4 C cooling that occurred during the time of the Mauder Minimum is indeed significant. It does suggest that a 2.0 C increase would result in very significant changes. That is indeed the concern.

A recent SkS item here presents the case that 2.0 degrees C should be considered an increase of significant concern and be the upper limits of impacts resulting from policy makers decisions of actions to be taken. Earlier reports have indicated that even a 1.5 C increase would lead to significant and difficult to forecast rapid changes of regional climate. Those changes could be difficult to effectively adapt to regionally since they would be changing so rapidly. At Copenhagen in 2009 global leaders had to admit that the lack of action by the already developed highest impact people, including the increased impacts of a dastardly few who already were very fortunate, had made a 1.5 C limit virtually impossible to achieve.

So 2.0 C is not just a concern it is a serious concern. Exceeding it is not considered to be decent, however, as has been stated, it would be even less acceptable to declare that since the impacts to date are so significant there is no reason for any attempts to reduce the impacts that the highest impact people of this generation have on future generations.

The current atmospheric concentration level of greenhouse gases has put in place a blanket that is causing irreversible global warming. The objective of the so-called 2 degree of warming is meaningless.The degree of warming will coninue to increase even if the rate of greenhouse emissions slow down due to decisions made and implemeted by governments. Ironically, the absorption of heat by the oceans will only slow the atmospheric heating down slighlty while the absorption of some of the greenhouse gases is causing the damaging ocean acidification.

denisaf,

You are correct about the damage to the ocean due to excess CO2 being absorbed. And the ocean is taking in a large amount of heat energy, however, because it is such a large mass it has not gotten very much warmer. A very small amount of ocean warming represents a huge amount of energy. However, the temperature will not continue to rise is humans curtail the creation of excess CO2 acummulation in the atmosphere.

The extra CO2 simply absorbs more infrared radiation that is being emitted by the planet surface. There is always a balance point when the warmer surface is emitting enough extra infrared to balance with the incoming solar radiation.

Though the excess CO2 that has accumulated in the atmosphere (most of the excess is being absorbed in the oceans), is expected to persist as excess for a very long time before it naturally gets lowered, the global average surface temperature will reach a 'balanced energy state' (balancing solar energy in with emitted energy getting out through the thicker CO2 'blanket'), at any level of CO2. It is expected to take at least 10 years for the 'balanced state' to be established for any level of CO2. However, if the excess CO2 concentration stops increasing the global average is expected to also stop increasing. So it is possible for human activity to change in ways that will reduce the future impact.

OPOF, what is the source for your last claim. It would seem to contradict recent work by MacDougal et al. and other papers that take carbon feedback into account, unlike most earlier models.

wili,

The current CO2 levels have not locked in endless increase in temperature. What has been locked-in is a long-term feedback response system which will raise temperatures for several decades before a balance condition is reached. The current CO2 levels will not lead to an endless always increasing temperature, just like the 280 ppm level over the past 1000 years had not caused endlessly increasing global average temepratures.

So curtailing the addition of CO2 by curtailing the burning of buried hydrocarbons is the most important thing to do. And once humans stop adding CO2 from that activity the eventual maximum global average impact will have been established, and it will be reached several decades later as the feedbacks collectively develop a new balanced condition. However, other changes of human activity can actually reduce atmospheric CO2 levels by things like:

A more difficult thing to evaluate is the potential for the feedbacks to collectively lead to very significant additional rapid changes resulting in the new balanced point being extremely magnified beyond the simple additional CO2 impact. Mann and others have repeatedly tried to raise awarenss of this concern so that policy makers do not get the idea that it is OK to shift to a higher target of human impact if we don't want to limit things to 2.0 degrees C.

The lack of action by the biggest impacting humans since 1990, when there was no doubt about the need to reduce the human impacts, resulted in a limit of 1.5 C being virtually unachievable by 2009. As much as I agree with the point that a continued lack of concern by current generations resulting in 2.0 C being unachievable would be no reason to stop trying to limit the impact, it is very dangerous to imply that it would be reasonable and decent or acceptably 'pragmatic' (a work I despise being applied to the knuckle-dragging done by many 'leaders' regarding this issue), for a current generation to decide 'it is too hard' for them to do what 'needs' to be done. The real problem is that the need is a future need. The current socioeconomic system encourages too many people to only care about their current 'desires' even making some people believe the 'desires' are 'needs'.